This past November, as the global death toll of COVID ticked past 5 million, the world gaped anew at the scale of pandemic loss. Yet the real toll of COVID is still more staggering — likely up to twice the number reported, say experts in infectious disease.

In the United States, 2.8 million Americans died between March 2020 and January 2021. More than 600,000 of those deaths were documented COVID cases. But an additional 522,368 are considered “excess deaths” — defined by the CDC as “the difference between the observed numbers of deaths in specific time periods and expected numbers of deaths in the same time periods.” These were deaths due to disruptions in healthcare, economic stress, mental-health crises, and undocumented COVID cases. Together, the COVID deaths and “excess deaths” reduced average life expectancy in the United States by nearly two years — a decline much sharper than those in other high-income countries.

The drop in life expectancy — a measure of how long people might expect to live, given the age-specific mortality rates of the period studied — was especially pronounced among Black and Latinx Americans. Recently, the National Cancer Institute (NCI), part of the National Institutes of Health (NIH), looked more closely at excess deaths between March 2020 and January 2021. After adjusting for age, scientists found that the number of Black and American Indian/Alaska Native deaths was three to four times higher than the number of white and Asian deaths, while Latinx deaths were nearly twice the number of white and Asian deaths.

“Focusing on COVID-19 deaths alone without examining total excess deaths … may underestimate the true impact of the pandemic,” said Meredith Shiels, the NCI senior investigator who led the study. “These data highlight the profound impact of long-standing inequities.”

The circumstances of these “COVID-adjacent” deaths are wide-ranging — from difficulty accessing health care in overwhelmed medical systems; to poor handling of chronic health conditions; to the pandemic’s psychological effects, with increased rates of depression, anxiety, suicide, and drug use. But together, they highlight a need for reform, both in our brick and mortar clinics and hospitals and in the reach and efficacy of virtual health support.

Accessing Health Care

More than one-third of health-care professionals report that the pandemic has worsened the health of patients with chronic conditions. According to the CDC, by June 30, 2020, 41 percent of American adults had delayed or avoided medical care — including urgent care — due to COVID concerns. As a result of delayed or inaccessible care, many patients with chronic conditions became sicker.

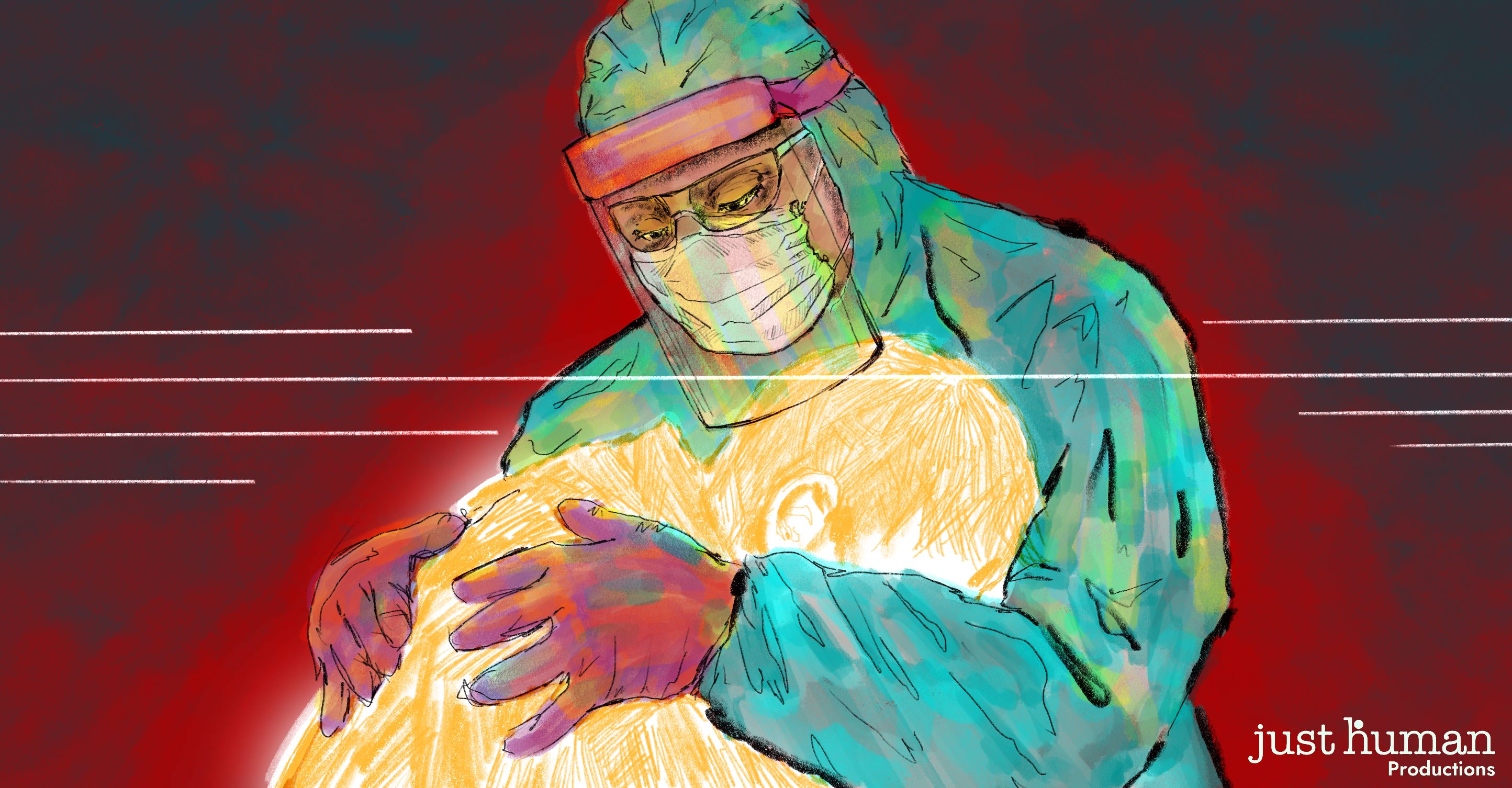

Throughout the world, onslaughts of COVID cases have left hospitals and medical professionals struggling to provide resources, facilities, and support. At the height of the pandemic, over 130,000 COVID patients required hospitalization each day, leaving even well-resourced hospitals overwhelmed.

With medical professionals and resources often diverted to assist COVID patients, others found their access to procedures and care curtailed. Non-COVID patients were frequently treated via telemedicine, and while many reported satisfaction with their experiences, telemedicine was not always an adequate replacement for in-person care. For those without internet access, as well as for some people with disabilities, virtual medicine could put health care out of reach.

Mental Health and Suicide

The pandemic’s reverberations — including job loss, chronic stress, social isolation, and the disruption of school and childcare routines — put novel and steady strains on many people’s mental health. Economic stress, in particular, has increased rates of depression among adults.

“One of the things that has been most striking to me as a psychiatrist is realizing how much of the depression we’re seeing is driven by economics,” says Dr. Roy Perlis, a psychiatry professor at Harvard Medical School who’s been a principal investigator on the COVID States Project, a national survey of about 20,000 people each month.

“You’re about 20 percent more likely to have symptoms of depression if … you’re behind on your rent,” says Perlis on Episode 59. “You’re more than 20 percent more likely to have depressive symptoms if … you’ve been evicted. About 10 to 15 percent more likely to tell us that you’re depressed if you’ve had to cut down on your work, because your hours were reduced or your wages were reduced.”

Among younger populations — specifically, teenagers and young adults — Perlis reports increases in depression, anxiety, and suicidal thinking. Up to one-third of 18-to-24-year-olds in Perlis’s surveys have reported suicidal thoughts — a rate five to 10 times higher than normal.

Perlis notes the loss of structural supports for this group during the pandemic, as many high schools and colleges shifted to virtual-learning mode. “For a lot of [young adults], their first contact with any sort of mental-health care is wandering into student health and talking to someone,” says Perlis. “And that’s a lot harder to do when you’re going to school on Zoom.”

But once that initial contact is made, says Perlis, telemedicine has seemed to work well for mental-health care. “Patients embrace it; clinicians, including psychiatrists, really find it pretty effective.” Perlis says that at his hospital, no-show rates for psychiatry outpatient programs have decreased significantly, because joining an appointment via Zoom is typically easier than traveling to a doctor’s office.

Yet as with primary care, not all those who are struggling have access to professionals — or to a stable internet connection and a quiet place to talk. And even for those who are well-equipped for the logistics of telemedicine, virtual mental-health care is at times insufficient.

Drug Overdoses

NPR reports that more than 93,000 people died from drug overdoses in the United States last year — a nearly 30 percent increase from 2019. “This is the highest number of overdose deaths ever recorded in a 12-month period, and the largest increase since at least 1999,” Dr. Nora Volkow, director of the National Institute on Drug Abuse, told NPR.

On Episode 58 of EPIDEMIC, Dr. Will Cooke discusses drug overdoses during the pandemic. Cooke is the author of Canary In The Coal Mine, which focuses on the national response to the opioid epidemic and Cooke’s own experience as the sole medical doctor in Austin, Indiana. “When the pandemic hit, our recovery groups shut down,” he says, adding that online support groups proved far less effective.

Cooke attributes a rise in relapse rates, in part, to the loss of community during COVID. “It’s when people start isolating that they are at the most risk for relapsing,” he says. “And we all basically had to isolate because of what was going on with the spread of COVID-19.” As people lost support systems that had provided them with “hope, opportunity, community, and recovery,” says Cooke, many turned back to opioids.

More people died from drug overdoses in 2020 than in any other year — evidence that the systems in place to help those struggling with addiction do not always translate well to a virtual world. In an NPR interview, Chuck Ingoglia, CEO of the National Council for Mental Wellbeing, explains that the federal response “prioritiz[es] the full continuum of interventions, everything from harm reduction to increased treatment capacity.” But without “long-term funding to create a system to address drug addiction,” he says, overdose rates may be hard to budge.

The pandemic has spurred a mortality crisis — and not just because of the lethality of COVID itself. While the COVID vaccine is effective in preventing severe viral illness and death, excess COVID deaths are preventable only by systemic change — the reform of both primary care and mental-health care systems, ensuring prompt and equitable access to the services patients need.