S1E49: Lessons from the Zombie Apocalypse / Coltan Scrivner, David Schnieder, Robert Wonser

“We have this long history of seeking personal and individual solutions to public problems and I think the zombie films highlight that.” – Robert Wonser

From Night of the Living Dead, to 28 Days Later, and World War Z, pandemics have always been at the heart of zombie movies. In this Halloween edition of Epidemic, we find out what these films get right and wrong about the current coronavirus pandemic, what they can teach us about epidemiology, and how fans of horror movies are experiencing the pandemic differently than the rest of us.

This podcast was created by Just Human Productions. We’re powered and distributed by Simplecast. We’re supported, in part, by listeners like you.

Celine Gounder: So, for people who are having a really hard time with the pandemic for one reason or another, maybe they’re very anxious or they’re lonely, should clinical psychologists be prescribing horror films to them?

Coltan Scrivner: [laughs] Prescribing Stephen King for the pandemic?

Celine Gounder: Welcome back to EPIDEMIC, the podcast about the science, public health, and social impacts of the coronavirus pandemic. I’m your host, Dr. Celine Gounder.

In the summer of 2009, the U.S. military developed a special training plan to confront an unprecedented threat.

Voice: This document contains information affecting the national defense of the United States within the meaning of the Espionage Laws, title 18, United States Code, sections 793 and 794. The transmission or revelation of information contained herein, in any manner, to an unauthorized person is prohibited by law…

Celine Gounder: This plan is now unclassified and was released to the public in 2011. It’s name: CONPLAN – 8888

Voice: This plan fulfills fictional contingency planning guidance tasking for US Strategic Command to develop a comprehensive Level 3 plan to undertake military operations to preserve non-zombie humans from threats posed by a zombie horde.

Celine Gounder: Zombies. The military came up with a plan to protect the nation from zombies.

Voice: The objective of the plan is three-fold… One: Establish and maintain a vigilant defensive condition aimed at protecting human kind from zombies…. Two: If necessary, conduct operations that will, if directed, eradicate zombie threats to human safety… Three: Aid civil authorities in maintaining law and order and restoring basic services during and after a zombie attack…

Celine Gounder: The plan covers pathogenic zombies… radiation zombies… space zombies… even chicken zombies? But this wasn’t a joke. Zombies may not be real, but the military realized the response to a make-believe enemy would be the same as a real threat. The CDC also has a zombie simulation.

Coltan Scrivner: It makes it more interesting, right? Like if you asked me, do I want to read the CDC’s plan for how to prepare for pandemic? I’m probably going to say no, but if you asked me, do I want to read the CDC’s plan for how to prevent zombies from taking over the world, I might say yes. Right? So, it is a nice way of kind of getting people interested in, in information that you’re trying to give them.

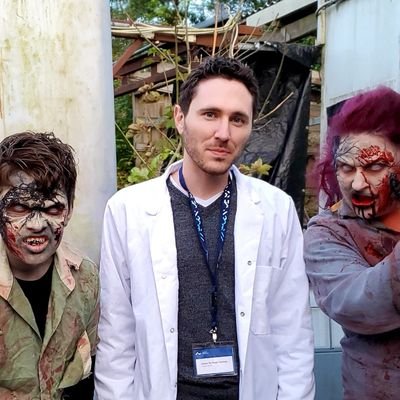

Celine Gounder: This is Coltan Scrivner. He’s a Ph.D. candidate in the Department of Comparative Human Development at the University of Chicago.

Coltan Scrivner: I think the only thing that I’m disappointed in is that somebody got to it before me, because I would love to have Department of Defense funding [Celine laughs] to come up with a plan to prevent a zombie outbreak [laughs].

Celine Gounder: Pandemics of all kinds — real or zombie — were on people’s minds when the coronavirus reached the United States.

Coltan Scrivner: The movie Contagion, which you know, was at that time, like nine years old, became one of the most watched movies in the US. So why, why would people watch, you know, why would you watch a movie about a pandemic when there’s a real pandemic?

Celine Gounder: Coltan was the lead author of an article that came out this summer. It asked why people were watching these movies all the sudden… and… if it signaled something deeper. In this Halloween edition of EPIDEMIC, we’re going to talk to experts in epidemiology and the social sciences to see how zombie movies — yes, zombie movies — can help us understand the pandemic. Zombie and other horror movies can help explain the fundamentals of epidemiology.

David Schnieder: Vampires tend to have a really low R0. And that’s compared to say, uh, zombies where they have a really high R0 and one zombie can bite many, many people and infect them all.

Celine Gounder: They anticipate some of the real problems we’re facing now.

Robert Wonser: We have this long history seeking personal and impersonal solutions to public problems, to social problems. And, I think the Zombie problems highlight that.

Celine Gounder: And… if you’re someone who likes zombie movies… there’s a chance you’re handling the pandemic better than most.

Coltan Scrivner: It’s sort of like, they dose themselves with self exposure, it’s like exposure therapy with horror films.

Celine Gounder; Today on EPIDEMIC… the coronavirus pandemic…. and zombies.

Coltan studies morbid curiosity.

Coltan Scrivner: [laughs] I think when I tell people that I study morbid curiosity at first, they kind of laugh and think I’m joking. But fortunately at U. Chicago they’re… they’re pretty supportive of obscure research.

Celine Gounder: Believe it or not, there’s not a lot of work in this area. He’s still trying to nail down a good definition.

Coltan Scrivner: It’s sort of an internal motivation to learn about threatening phenomena, or situations in your environment that might be threatening.

Celine Gounder: Coltan identified four categories of morbid curiosity. Interpersonal violence:

Coltan Scrivner: So this means anything from the Romans going to the Coliseum, or if a street fight breaks out everyone stops and looks, right?

Celine Gounder: Supernatural:

Coltan Scrivner: This would be sort of your typical ghost story or monster story.

Celine Gounder: Body violation:

ColtanScrivner: And so this could be something like an interest in, uh, surgeries or, you know, people post YouTube videos of surgeries and they get, you know, millions of views.

Celine Gounder: And the motives of dangerous people:

Coltan Scrivner: And so this sort of is just basically like true crime. So you’re interested in learning about the minds of people who are dangerous around you. The unifying thread through each of these four facets is a motivation to learn about dangerous phenomena or situations in your environment.

Celine Gounder: So when the pandemic happened, it presented Coltan with a unique opportunity to study morbid curiosity on a grand scale. Back in March, one of his colleagues got a tweet asking, are horror fans doing better during the pandemic? Coltan and his colleagues had been thinking that maybe horror fans were better able to cope with real-world fears and anxiety. But no one had ever done any studies on it.

Coltan Scrivner: He and I talked about it and thought, well this is a really interesting question. It’s something, you know, we’ve thought about, uh, let’s study it because now we have the opportunity to study this exact thing.

Celine Gounder: Coltan and three colleagues put together a study to see if horror fans were more psychologically resilient during the pandemic. So, what does it even mean to be psychologically resilient?

Coltan Scrivner: Yeah, so that’s a, that’s a really good question because that’s something that we had trouble with, who we were designing this study because there are a lot of different kinds of definitions of psychological resilience. Basically the idea is there are two aspects to this long drawn out resilience. There’s a psychological distress, which you would want to be low on. So this would mean that if you’re low on psychological distress, you’re experiencing fewer symptoms of anxiety, of depression, sleeplessness, irritability. And then there’s positive resilience and positive resilience, uh, sort of characterized by ability to enjoy life when things are rough. Right? So you’re able to find things you enjoy doing, even if there’s a pandemic, even if it’s causing you a lot of grief.

Celine Gounder: They asked more than 300 people three sets of questions. The first questionnaire was designed to see how psychologically resilient respondents were during the pandemic. The second was a morbid curiosity survey. And the third was a survey for what kinds of movies they preferred.

Coltan Scrivner: So we asked them broad genre questions, like core romance and comedy. And then we asked, uh, some specific ones as well. So we took apocalyptic films, alien invasion, and zombie films, and we lump those together into something we called “prepper genres.” You know, the institutions that people rely on are no longer functioning, like they normally would. And so we thought this sort of best captured what happens during a global pandemic.

Celine Gounder: But before we hear the results of the study, we’re going to see how zombie movies can help explain the basics of epidemiology. The same things that make a zombie apocalypse a good training simulation for the military, also make it useful for explaining concepts in science.

David Schneider: I watched movies that make me anxious about real things that, you know, I might encounter. And then it helps me think about how these things would work. So I like, I liked the disease, sort of disease-based horror films.

Celine Gounder: David Schneider is a professor of microbiology and immunology at Stanford University. When he first started teaching there, he created a class that used horror films to teach students about epidemiology.

David Schneider: It allows you to separate it and put it in a sandbox where it’s really pretty safe to describe. And then the way the diseases are transmitted, they’re usually artificial and not things that we have to worry about, you know, being bitten by a zombie or something like that.

Celine Gounder: Zombie bites are actually a really good way to explain a concept in epidemiology a lot of people have been hearing lately. The basic reproduction number of a virus or R0.

David Schneider: Yeah. So R0, is the, um, rate that an infected person is likely to pass on the disease to an uninfected person.

Celine Gounder: If the “R” of an infected person is less than zero, the rate of transmission falls. But if it’s higher than zero… well, that means it can spread fast. The SARS-CoV-2 virus, for example, can have an R0 as high as three; smallpox, six; and measles, fifteen. The R0 is a characteristic of both the virus… and of what we do to control it.

David Schneider: This shows up in different ways in movies. So you have, vampires, which, exist by, sitting quietly in society at a level where they’re basically undetected and they will feed on humans, But they don’t spawn new vampires very frequently because that would give them competition, uh, and it would also make them more noticeable. So vampires tend to have a really low R0. Just enough to keep them going, but they aren’t going to increase their numbers. And that’s compared to say, zombies where they have a really high R0 and one zombie can bite many, many people and infect them all.

Celine Gounder: The Rage virus in 28 Days Later is a good example of this. The R0 of that virus is so high, infection is instant. But if the virus spreads too fast and kills too many of its hosts… it dies out.

David Schneider:With that really high R0, it’s going to destroy humanity and then the virus will, will disappear. So I would expect that over time zombies would become less virulent.

Celine Gounder: Another twist on epidemiology in horror films is disease tolerance. The 1954 novel I am Legend that inspired the film of the same name deals with this. Spoilers ahead, FYI.The novel is about a virus that wipes out most of humanity and turns the survivors into these vampire-zombie creatures. The last man on earth who’s uninfected has been killing the monsters infected with the disease after he fails to develop a cure.

David Schneider: So he encounters a woman who appears not to have the disease and ends up falling in love with her. And it turns out this is a trap for him because he, he’s been killing people who he thought had the disease, but some of them actually survived quite well as humans. And he’s actually wiping out humanity. So these infected people end up setting a trap for him so they can kill him so that humanity survives. And, and we see this really strongly with COVID, you know, there’s some populations of people where COVID is a highly deadly disease, and there are other populations of people where it’s really not.

Celine Gounder: Some people’s immune systems do a better job at fending off COVID. But anyone with SARS-CoV-2 can spread the infection…even if they don’t have symptoms. How’s that for a horror movie? This that’s why social isolation is so important to reduce the spread of the coronavirus… and, by the way, survive a zombie apocalypse.

Robert Wonser: It’s interesting when we look at, you know, who’s successful in fending off zombies, it’s people who are in highly cohesive groups that look out for each other, or it’s people who are socially isolated.

This is Robert Wonser. He’s a sociologist at College of the Canyons in Santa Clarita, California. Robert co-authored an article looking at how zombie films reflect the fears of the time when they were made.

Robert Wonser: And the fears change through time. So the fears of Cold War, the fears of, uh, space,and, and, um, technology gone awry, uh, in recent years with like the Resident Evil films, you get the rise of evil corporations.

Celine Gounder: Another is income inequality. In zombie movies and in real life, being able to socially isolate effectively comes down to a question of class. One of George Romero’s later zombie movies, Land of the Dead, explores these class divides in an extreme way. In that movie, Dennis Hopper plays the leader of a militarized compound called Fiddler’s Green, where an uber-wealthy elite live far removed from the zombie apocalypse outside.

Robert Wonser: He’s able to keep his distance from, you know, the potential harm. And it’s not just the zombie threat that’s kept at bay. It’s the poor who are kept out. And I mean, in, in the very real world too, we’re seeing that, who can afford to remain socially distant? Whose jobs allow them to work from home, who can afford to have, you know, DoorDash and GrubHub and Instacart deliver their groceries? And then who has no choice, but to be the person delivering those.

Celine Gounder: One thing zombie movies definitely don’t reflect is trust in institutions… especially the government.

Robert Wonser: Part of what makes a movie interesting is these rides. You know, nobody wants to watch a movie where things go smoothly and the government’s approach is flawless, and, you know, martial law doesn’t have to be declared cause everybody calmly waits at home with masks on and, and socially distance.

Celine Gounder: And the U.S. response to the pandemic has been anything but flawless. With little response from the federal government and some states, many communities and individuals were left on their own.

Celine Gounder: Having to survive on your own is a common theme in zombie movies. And it usually doesn’t encourage a warm picture of your fellow human beings. The prepper films Coltan Scrivner talked about in his study usually assume the worst about people. Hoarding food and toilet paper at the beginning of the pandemic seemed right in line with this. But Robert pointed out that there’s a lot of horror films that got wrong about the pandemic.

Robert Wonser: Contrary to the, every man for himself, we saw a lot of people coming together. The problem of course, is that it’s not a systemic approach. You know, it relies on social capital, you know, do you have access to people who can help you? Um, are the people in your social network wealthy enough to donate to your GoFund me? We have this long history of seeking personal and individual solutions to public problems to social problems. And I think the zombie films highlight that.

Celine Gounder: Robert says we could see these zombie films as cautionary tales.

Robert Wonser: You know, I think the takeaway in those films of, of what usually brings success is cooperation, and lack of belligerence. You know, like we don’t assume the worst in everybody. The Walking Dead is famous for taking all of the moral characters and having them be shown to be completely wrong. And, you know, the, the really terrible people are the ones who end up surviving. And while there is certainly precedent for that in, in real life, I think, you know, when you look at, um, history and what leads to success it’s some sort of cooperation.

Celine Gounder: Robert has been watching a lot of these movies during the pandemic.

Robert Wonser: My wife and I watched the movie Contagion, like five times since the pandemic started. Um, and I always started that movie as a zombie movie minus the zombies.

Celine Gounder: I will confess, I did go back and I watched Contagion. I went back and watched Outbreak. I watched World War Z and maybe one or two others at the beginning of the pandemic. But you said five times. What’s the reason for watching that so many times in the midst of what we’re dealing with right now?

Robert Wonser: Yeah. Um, and I’m guessing at five, it was definitely more than one. Uh, but, uh if I had to pin it down, I’m sure there’s some reassurance and, uh, fictionalized accounts that are, you know, reflective of real life.

Celine Gounder: Coltan Scrivner says this is normal.

Coltan Scrivner: A lot of people say, uh, you know, the reason that it helps me cope is because I watched the movie Contagion and I see that, you know, the virus in that had like a 30% mortality rate. And I just think, Oh, well, COVID, isn’t as bad as that. So I think people do that even with movies, right? Or even with books. They see these examples of how bad things could be and even through simulation that might help them sort of overcome feelings that their, uh, feelings of dread that they might have about some specific problem in their life.

Celine Gounder: Zombies or pandemic movies are a way to tap into the fear from the comfort of your couch. The results of Coltan’s study explain why.

Coltan Scrivner: Yeah, so there were four, I guess, main findings, or four sort of cornerstone findings. The first one was that horror fans were more likely to say that they were having fewer symptoms of psychological distress than non-horror fans. So they were experiencing, you know, less anxiety, fewer sleepless nights, things like that.

Celine Gounder: The study also found that people who were fans of the prepper films — movies like zombie pandemics and alien invasion — they said they felt less psychological distress but they also felt more prepared for the pandemic.

Coltan Scrivner: People who watched, it wasn’t like you had to be a hardcore, you know, pandemic movie fan. But if you just watched a few of them, you were, you felt significantly more prepared for the pandemic than people who had never watched any of them.

Celine Gounder: But the reason those respondents reported doing better during the pandemic wasn’t because they had fewer signs of psychological distress.

Coltan Scrivner: Basically people who are morbidly curious were able to find ways to enjoy their life during the pandemic. You know, again, even though it was terrible and it might be, you know, might’ve caused them to lose their job or, you know, they’re afraid that they might, uh, catch coronavirus, they’re still able to find something interesting about it. People who are morbidly curious are not less afraid of violence. They’re not less afraid of the pandemic. They’re not less afraid of dangerous people. They’re just more interested in it

Celine Gounder: Coltan says his own morbid curiosity has helped him deal with the stresses of the pandemic.

Coltan Scrivner: There are lots of aspects of COVID that are interesting to me, you know, that the societal implications are interesting to me. The psychological implications are interesting to me. The virology is interesting to me. And so when I am inundated with COVID news, I’m usually able to find something about it that kind of peaks my interest. And I think that’s been really helpful.

Celine Gounder: So for, for people who are having a really hard time with the pandemic for one reason or another, maybe they’re very anxious or they’re lonely. Should clinical psychologists be prescribing horror films to them?

Coltan Scrivner: [laughs] Prescribing Stephen King for the pandemic? Um… It’s not the case that you watch one horror film and now you’re, you’re good to go for round two of COVID. But rather that, because you’ve exposed yourself to these sort of scary situations on time, you’ve developed better regulation skills. And so when you’re exposed to something in the real world that’s scary or is anxiety inducing, you’re better able to deal with that.

Celine Gounder: There’s a lot to be afraid of in the middle of a pandemic, but at least we know, these movies are nothing to be afraid of, right?

Celine Gounder: “Epidemic” is brought to you by Just Human Productions. We’re funded in part by listeners like you. We’re powered and distributed by Simplecast.

Today’s episode was produced by Zach Dyer and me. Our music is by the Blue Dot Sessions. Our interns are Tabata Gordillo, Annabel Chen, and Bryan Chen.

Special thanks to Alain Pierre for reading excerpts of CONPLAN-8888.

If you enjoy the show, please tell a friend about it today. And if you haven’t already done so, leave us a review on Apple Podcasts. It helps more people find out about the show!

You can learn more about this podcast, how to engage with us on social media, and how to support the podcast at epidemic.fm. That’s epidemic.fm. Just Human Productions is a 501(c)(3) non-profit organization, so your donations to support our podcasts are tax-deductible. Go to epidemic.fm to make a donation.

We release “Epidemic” every Friday. But producing a podcast costs money… we’ve got to pay our staff! So please make a donation to help us keep this going.

And check out our sister podcast “American Diagnosis.” You can find it wherever you listen to podcasts or at americandiagnosis.fm. On “American Diagnosis,” we cover some of the biggest public health challenges affecting the nation today. In Season 1, we covered youth and mental health; in season 2, the opioid overdose crisis; and in season 3, gun violence in America.

I’m Dr. Celine Gounder. Thanks for listening to “Epidemic.”