- In a recent survey, 4 in 10 rural Americans reported getting at least their first dose of the vaccine — a higher rate than the suburban-urban average of 3 in 10.

- “You’re somewhat emotionally exhausted because you’ve given a lot at the end of the day, but you’re also on top of the world. It’s a mixture of feelings,” recalls Dana Friend, a volunteer at vaccination sites in West Virginia.

- Rural Americans’ most common vaccine concerns include safety, side effects, and the details of vaccine development.

Anna Loge calls her hometown of Dillon — big skies, wide open valleys, a view of the Rockies — “as classic Montana as you possibly can get.” For the past ten years, she’s been a general internist at Dillon’s critical-care hospital — and in the midst of Dillon’s clear vistas and deeply familiar landscape, COVID-19 was a strange and ominous specter. When the hospital’s first COVID case showed up in March of 2020, she says, “We very much realized we were dealing with something we had never seen before.”

What followed was a mix of the worry, regulations, and resistance that have gripped towns and cities nationwide. But rural communities like Dillon, home to about 5,000 people, have often been sites of particular ambivalence and fierce pushback, with many residents simply not seeing the pandemic as a threat. Already “socially distanced” in some ways, and far from the factories and packed subways that can seem like cauldrons of contagion, many have felt more riled up by mask mandates and school closures than by the virus itself.

Loge recalls contentious public meetings, fury over masks, and a politicization of the virus that often made it hard to get out messages about the safety and side effects of vaccines. “There is still this strong sense that [COVID]’s not that big of a deal, [that] all of these restrictions seem to be a bit overblown,” she says. “And that’s a hard narrative to … work within — or maybe even sometimes, work against — to try to do the best for our community and for our patients.”

Still, Dillon’s health workers quickly figured out COVID procedures, and in recent months, Montana has become one of the leading states in vaccination rates. Despite a common misconception that rural communities have low vaccination rates, a recent survey by the Kaiser Family Foundation shows that 4 in 10 rural Americans reported getting at least their first dose of the vaccine, compared to 3 in 10 in urban and suburban areas.

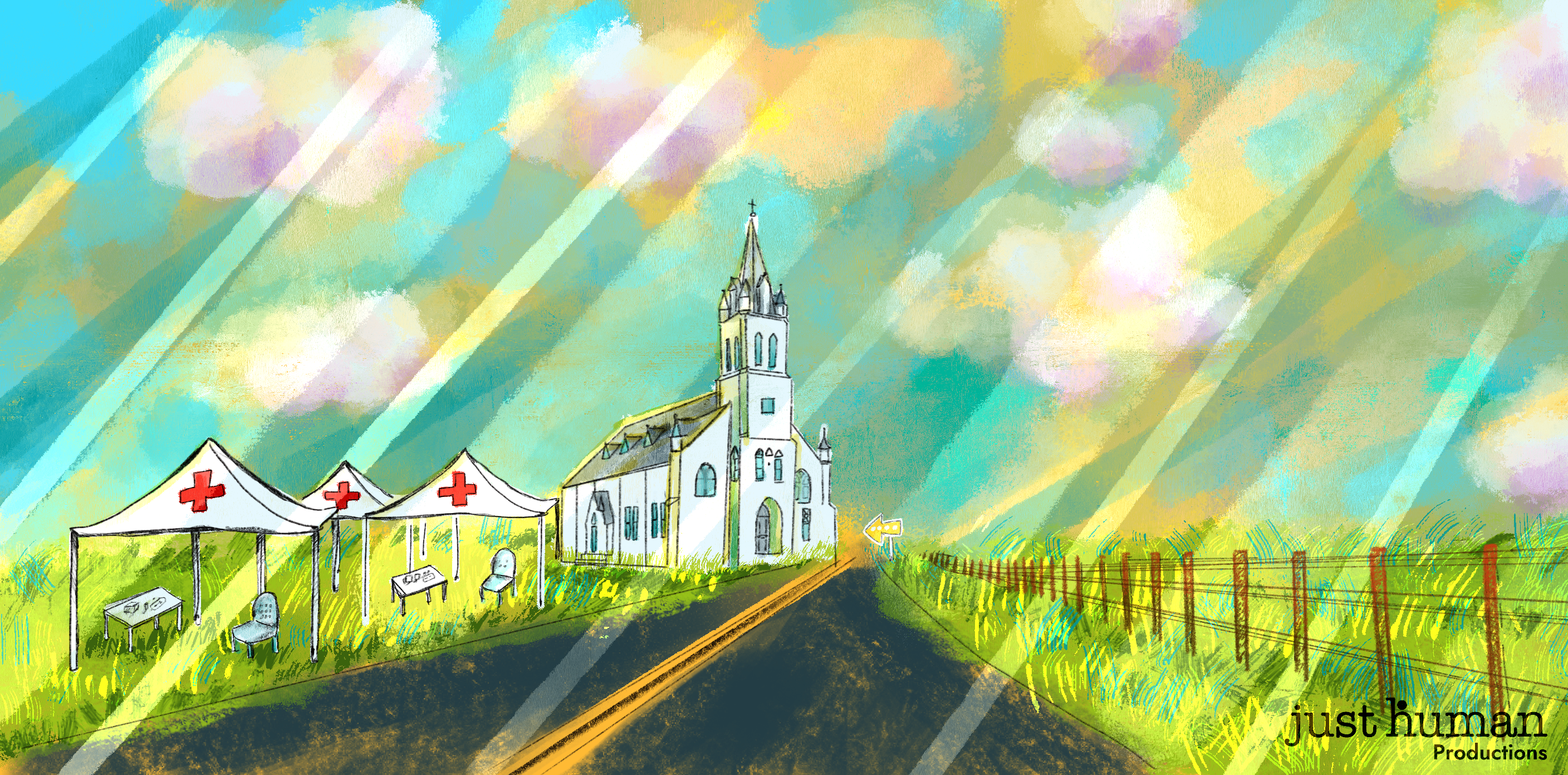

In episode 70 of EPIDEMIC, Country In-Roads: Building Vaccine Confidence in Rural America, rural healthcare workers explore the successes and challenges of the vaccination rollout in their communities.

Challenges in access

In a town as small as Dillon, almost everyone knows someone who has been infected with COVID. Yet many don’t see COVID as a big concern. Loge explains: “I more often hear them say, ‘Well, so-and-so had it, and they didn’t get really sick.’”

Over the past year, Loge has dedicated herself to challenging this narrative, talking with Dillon residents one-on-one about vaccine development, safety, and side effects. The key to these discussions, Loge says, “is to listen to their concerns and then talk through the science.” She estimates that three out of four people who’ve come to her with concerns have ended up getting vaccinated.

But Dillon ran into another major barrier in the vaccination process: access. Living in a rural town means you’re far from major cities, forcing many residents to drive hours to a vaccination site. As a solution, county health nurses organized local immunization clinics every Friday. The consistency of location and timing helped, says Loge, and as a result of the Friday clinics, “over 70% of our patients over the age of seventy have received at least one immunization.”

Adapting for the needs of rural communities

Not all rural communities have access to the same medical facilities as Dillon, with its critical-care hospital. Some have only one small provider. Elizabeth Ellis is a family nurse practitioner and owns an accredited health clinic in Bedias, Texas, which is home to fewer than four hundred people. Ellis’s clinic is the only one for miles.

In order to increase access to the vaccine, Texas created vaccine centers across the state called “hubs.” But the closest hub to Bedias was an hour’s drive. Many residents did not have transportation to make that trip, or reliable internet access, computers, and cell service to schedule appointments.

Ellis decided the only reasonable solution was for her to distribute vaccines herself. The Pfizer vaccine had to be kept at ultra-cold temperatures, which Ellis couldn’t do. But her clinic could handle the Moderna vaccine, so she requested one hundred doses. Ellis received one hundred vaccine doses on January 11th, and with help from volunteer health-care workers and members of the local Baptist church, she administered all the doses in one week.

But the Moderna vaccine requires two rounds, and Ellis didn’t yet have access to the second dose. So she called state health officials. Once they heard she was the only provider in her county, they promised her hundred second-round doses — and even sent in the National Guard to help administer them.

Then the Texas winter storm blew through on February 11th, leaving nearly 4.5 million homes and businesses without power. That same day, FedEx showed up at Ellis’s clinic with not only the second doses she had requested, but also an extra hundred doses. Ellis and her team spent the next couple of nights recruiting two hundred people to be vaccinated — in a town of fewer than four hundred. Many residents heard about the vaccines through church organizations, community leaders, and local officials; Ellis even ran over to the post office to recruit patients, making sure no vaccination went to waste. She managed to administer all two hundred doses in a day.

Still, challenges continue: A site change for the second dose has prompted cancellations. Some people don’t want the second dose; others can’t take time off work for the Wednesday vaccination clinic. Still, Ellis hopes that community members who are already vaccinated will spread the word and encourage others to get vaccinated, too.

‘You feel like it’s a piece of gold’

Just as the vaccines themselves can transform people’s sense of what they might safely do, working at vaccination sites is, for many, a powerful experience. Dana Friend is a nurse at the West Virginia School of Nursing, and has volunteered at a variety of vaccination sites in West Virginia. She recalls a transcendent moment when she administered her first vaccine: “You feel like it’s a piece of gold, almost. You have this beautiful vaccine that can help us move forward and to help us to regain a new normal.”

Friend’s husband, Chris Martin, is a professor at West Virginia University’s School of Public Health and director of the school’s Global Engagement Office for the Health Sciences Center. Martin says West Virginia had a lot to be concerned about when COVID hit. The state has a relatively older population and high rates of chronic conditions and obesity, all of which increase susceptibility to COVID. But like Dillion, West Virginia has challenged misconceptions about rural vaccination rates. In the beginning of COVID vaccine roll out, West Virginia led all other states in vaccination rates. The state opted out of a federal program that relied on national pharmacies to distribute vaccines. Instead, West Virginia relied on local pharmacies that were more evenly distributed throughout the state. Using local resources has been an effective — and necessary — strategy in rural areas such as Dillon, Bedias, and much of West Virginia.

Friend is a strong advocate for the small, local vaccination sites that have propelled West Virginia to the nation’s highest vaccination rates: “There was always so much gratitude, so much thankfulness and appreciation,” she says. And sometimes, a connection through time as well: Friend vaccinated one man who recalled getting the polio vaccine as a child — and his relief, back then, at no longer having to spend summers indoors, with his parents fearful he’d be crippled by the poliovirus. Those receiving COVID vaccines have often told Friend of their eagerness to spend time with family and loved ones, too, released from worries of contagion that have dogged them during the pandemic.

So far, most of those eligible for vaccination have been high-risk and essential workers; it remains to be seen whether younger people show up at similarly high rates in rural areas. But rural healthcare workers, like Friend, are hopeful: “It’s just a beautiful thing to be able to … provide,” she says.