A Black Man in Science Part II: The Pursuit of Truth / David Satcher / Kafui Dzirasa / Harold Varmus

“Science is harmed when scientists don’t take into account the bias that comes along with inherently being a human.” -Kafui Dzirasa

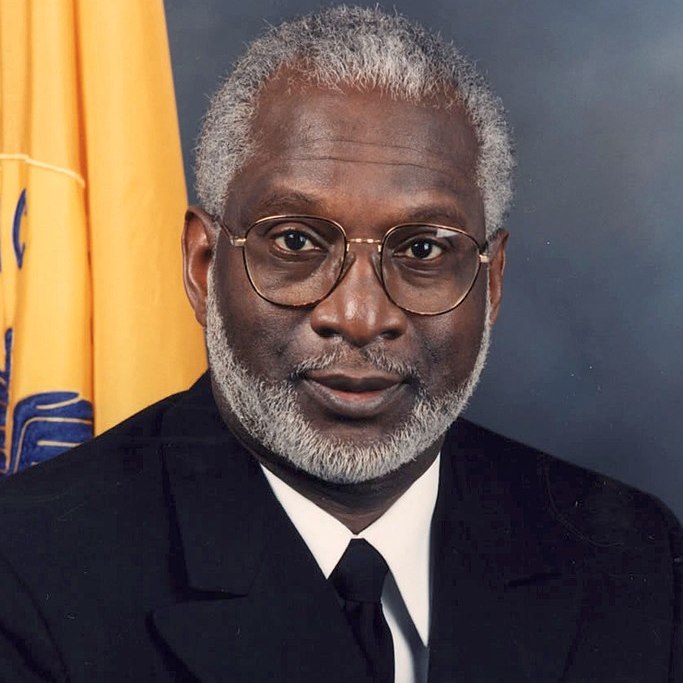

As a result of centuries of discrimination, and lack of access to education and opportunity, African Americans comprise only 5% of active physicians in the United States today. Former-Surgeon General David Satcher, who was also the first African American to lead the CDC, has been working to improve health equity in the United States since his days as a medical student in the 1960s. In this bonus episode of AMERICAN DIAGNOSIS, we’re going to hear about efforts to improve health equity in America from leaders like Dr. Satcher, former-NIH director Harold Varmus, and Kafui Dzirasa. We’ll see how they are seizing this critical moment for racial justice to improve health outcomes and professional opportunities for people of color in the sciences.

This podcast was created by Just Human Productions. We’re powered and distributed by Simplecast. We’re supported, in part, by listeners like you.

Harold Varmus: My father was a physician who had the resources that allowed me to go to a good, expensive, private college and a good medical school without worrying. That’s not true for most Blacks and Hispanics in this country.

Kafui Dzirasa: As our country continues to become more diverse, it is probably a bad idea if our country does not learn to better draw on the talent across our younger parts of the population.

Céline Gounder: Hi, everyone. Dr. Celine Gounder, here. I’m the host of AMERICAN DIAGNOSIS, the podcast about health and social justice.

The United States has always had a complicated history with inclusion. In fact, many prominent medical colleges didn’t admit their first Black students until the mid 1960s. I spoke about this with David Satcher, an American physician who went on to become Director of the CDC and, later, Surgeon General of the United States… despite having grown up in the segregated South.

David Satcher: Anniston, Alabama in the forties was a difficult town, especially for African-Americans because it was just assumed that African-Americans did not have access to the hospital.

Céline Gounder: When David was young, he contracted a serious case of whooping cough and pneumonia. David’s parents asked the only doctor in town if he’d be willing to see David, to save his life.

David Satcher: Dr. Jackson was the only black doctor in Anniston, came up there. And when he left, he explained to them that he didn’t expect me to live. He had done all he could do, but he didn’t expect me to live out the week.

Céline Gounder: But David did live… and his close brush with death inspired him to become a physician.

David Satcher: By the time of my sixth birthday, I was telling everybody that I was going to be a doctor just like Dr. Jackson.

Céline Gounder: After graduating from high school in 1959, David went on to attend Morehouse College, where he got involved in the student movement for civil rights.

David Satcher: We were determined to be non-violent. We couldn’t defend ourselves, but we went prepared for whatever was going to happen to us.

Céline Gounder: David recalls one time when he was arrested for sitting in a restaurant.

David Satcher: I was sent to prison, because by that time I was a leader among the students. And so we had planned to fill the jail. It was quite a movement to “fill the jails with students.”

Céline Gounder: David learned a lot about mobilizing from his active participation in the civil rights movement. But despite his passion for activism, doing well in school was foremost in his thoughts.

David Satcher: I try to make it very clear that I was a serious student. At no time did I take lightly my responsibility as a student, I often came out of jail and made one of the highest marks if we have an exam the next day. I remember about chemistry exam that we were so worried about. But I made the second highest grade on that exam after coming out of prison. So I, I was fortunate enough to be able to balance student activities with classroom.

Céline Gounder: After graduating from Morehouse, David set his eyes on Duke for medical school, which up until that point, had never admitted a Black student. But David was an all-star. He had great grades, he was involved in student activities, and he was popular among his peers. He was a shoo-in. And he got an interview.

David Satcher: I was excited about the interview. Morehouse alumni came out in great numbers to greet me when I went to Durham and I was there for a couple of days. And then, when I got the letter turning me down, it was a let down. I was actually depressed for a while. Duke did admit its first black student that year. And of course he, he had not been involved in the kind of student movement or going to jail or anything like that. So I’m sure from Duke’s perspective, it was not a very difficult choice.

Céline Gounder: As a result of decades, really centuries, of discrimination and lack of access to education and opportunity, African Americans comprise only 5% of active physicians in the United States today. As more and more African-Americans come forward with their own stories of medical racism, the conversation about ensuring that there are more doctors — and scientists — of color has become all the more urgent. More than half a century after David applied to Duke, we have yet to make much progress in getting more people of color into the sciences. But scientists of color are making strides to change that.

In this bonus episode of AMERICAN DIAGNOSIS, we’re going to hear more about David Satcher’s efforts to improve health equity in America. We’ll also return to Kafui Dzirasa, who we spoke to in a prior episode about being a Black man in science. We’ll see how he and others are trying to seize this critical moment for racial justice to improve health outcomes and professional opportunities for people of color in the sciences.

David did end up going to medical school. He attended Case Western Reserve University and enrolled in a seven-year dual MD and PhD program in 1963. But while there, David encountered methods of medical training that disturbed him.

David Satcher: Specifically, when I went back and the rotation was OB-GYN, and on the first day of the rotation, there were nine students in my group. I was the only Black, and we went into the room where they were going to teach us the pelvic exam. You know, obviously I noticed right away that the women who were there to be examined were all Black. And I think that had more to do with the fact that they could not pay for their care. And I think the rule then was that, you couldn’t pay then you agreed to participate in the teaching program.

Céline Gounder: Even today, people of color are more likely to end up on “public wards” at hospitals across the country, where physicians-in-training are given more autonomy to practice and learn from their mistakes.

David Satcher: There were not curtains and things to protect their privacy. I, I reacted to it, I thought these women were being mistreated and disrespected. And so I walked out.

Céline Gounder: David had spent his entire life working to become a physician, but what he saw in the hospital that day disgusted him, and he had to speak up.

David Satcher: The person who was head of the rotation was very upset that I would dare walk out on his rotation. He told me that he was going to make sure that I got put out of school, not just Case Western, but that I would never get into another medical school.

Céline Gounder: David was told to go meet with the Dean of the University the next morning.

David Satcher: And so when I sat down, he said, well, David, it seems like you’ve done yourself into some trouble. And I said, I guess so.

Céline Gounder: David was fully expecting to be expelled.

David Satcher: And then he said, well, do you know what happened this morning? I said, no, what happened? He said, well, the rest of the students walked out. They said, they agreed with you. They said it was inhumane the way the patients were being treated. And he said, you know, something David? We got to fix that program.

Céline Gounder: David graduated from Case Western Reserve University with a degree in cell biology in 1970. When he entered the workforce, he continued to exhibit the leadership skills and activism that defined his time in school. David went on to become the first Black Director of the CDC in 1993. He became Surgeon General in 1998. But Satcher was still a rare Black man in the sciences. All these years later, the number of Black people in the sciences remained stubbornly low. And David was not the only person who noticed this. Harold Varmus was Director of the National Institutes of Health in the 1990s. He, too, noticed this disparity.

Harold Varmus: The percentage of the scientific workforce that’s African-American or black is less than 2% and the Hispanic numbers are not much better. That, that is a real failing for a wide variety of reasons. It’s a failing because it deprives us of a large sector of the talent in this country. Uh, it’s a failing because we’re not taking advantage of people who bring a unique perspective to problems in minority health. It’s a problem because the very absence of a black and Hispanic scientist in the scientific community is a discouraging feature to people who think of thinking about undertaking the very difficult task of becoming a scientist.

Céline Gounder: Harold knows that for people of color, the decision to not study science is sometimes a financial one.

Harold Varmus: I had it extremely easily easy. I’m perhaps an obvious example of white privilege in this case. When I grew up, I never really thought about the expense of any of these things. I just did what I wanted to do. My father was a physician who had the resources that allowed me to go to a good, expensive, private college and a good medical school without worrying. That’s not true for most Blacks and Hispanics in this country, they don’t have the family resources from real estate and the legacies, and we’ve got to do something to protect them, so that we can allow people the freedom to pursue careers that they find attractive.

Céline Gounder: In the early 2000’s, David and Harold worked together to propose legislation creating a new institute at the NIH focused on disparities in health and medicine.

David Satcher: We were proposing legislation that would create the National Institute of Minority Health and Health Disparities that in fact, that would be legislation promoting the elimination of disparities in health. So Harold said to me, I want you to present to them the logic, just, as you presented to me, see what they think. As it turned out, they voted to support it. So Harold Varmus went before Congress and supported the legislation to reduce and ultimately eliminate disparities in health.

Céline Gounder: David also wanted to bring more people of color into science and medical research, but the legislation didn’t inspire the sort of change that David wanted to see.

David Satcher: Well, I think the word is incentives. We’ve got to reward success. We’ve got to provide incentives. We’ve got to make a long term commitment. I think basic to this problem is the fact that so many of our efforts are short term. And everybody knows that as soon as there’s a new administration, those efforts may go by the wayside.

Céline Gounder: I asked Harold to rate the progress that’s been made since he and David worked on this.

Harold Varmus: Well I think we probably deserve a C plus or a B minus for our work on health disparities, drawing the disparities to the attention of the public. And indeed, I have to say that, uh, the attention to those issues is, at its highest point ever as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic, because everybody is seeing and all parts of the country, the much greater burden of disease, that’s falling on people of color than on white people and that is making a very big impression.

Céline Gounder: After the break, we’ll hear what Harold Varmus and another scientist, Kaf Dzirasa, are doing to achieve today what Harold and David set out to do in the 1990s. Almost four decades after David was rejected from Duke University, Kaf Dzirasa, the child of two Ghanian immigrants, was the first African-American to graduate from Duke with a MD and a PhD in neurobiology. I spoke with Kaf in a previous episode about some of the challenges he faced being one of the few Black men attending medical school.

Kafui Dzirasa: “So, medical school was awful. And I had early intersections with faculty and advisory deans at Duke that sort of blended my experience of feeling like I was dumb and then all of the subtexts around race started showing up. You know, we would get slides, um, and they would teach us about diseases and things we should memorize. And I would repeatedly find that people that were sick with a certain disease type, they would always be paired with Black skin. And so it really begins to pair these things in ways that I say enforced this really complicated and really insidious history of medicine and science in this country.”

Céline Gounder: Kaf recalls that in med school many other students of color had to make hard choices about what fields to pursue.

Kafui Dzirasa: There was a reason that people are interested in certain fields like radiology and dermatology, and tend to angle away from subspecialties of medicine that tend to have lower compensation. Financial wealth tends to be highly correlated or associated with, racial and ethnic backgrounds in this country. And if you’re the first in your family to graduate from college, to graduate training with financial barriers of financial needs, this salary might not be enough to support you and your family. And so there are incredible pressures there that we would like to figure out how to alleviate.

Céline Gounder: Kaf made it a point to seek out mentors. One of those mentors was Harold Varmus. Harold had started following Kaf’s career closely even before they met.

Harold Varmus: One of the reasons I knew about Kaf is that he was one of the most prestigious graduates of a program called the Meyerhoff program.

Céline Gounder: The Meyerhoff Scholars program strives to increase diversity in the STEM fields. Students in the program receive full scholarship to study science and engineering at the University of Maryland, Baltimore County.

Harold Varmus: This group of students has been extraordinarily successful, virtually every one of them getting a PhD or an MD, many going on to have very, um, important and prominent, uh, research careers.

Céline Gounder: Over the summer, the George Floyd protests spurred Kaf to start working on a paper with Harold, which stresses the “the fierce urgency of now, to address the issues of diversity in science.”

Kafui Dzirasa: I think we’re at the confluence of two really important observations. One of them, and I think this was really motivated by George Floyd and the subsequent protests throughout the summer, is that this is just the right thing to do. Racism is wrong. Racism is present. It’s just the right, fair thing to do. I think we’re also at a time where it’s also becoming increasingly clear that this is the smart thing for our country to do. As our country continues to become more diverse, it is probably a bad idea if our country does not learn to better draw on the talent – the innate talent, that is across are the younger parts of the population.

Céline Gounder: Kaf wanted to work through his own personal experiences.

Kafui Dzirasa: One, I was motivated to write it because one of my own trainees was writing about her experience, and I wanted to make sure that, if there was any backlash to anything she had to say that that would come upon me, right? I felt I was a little bit further in my career and could sort of bear the inevitable backlash that comes when you try to bring about change. But in writing that piece, I really talked about, you know, some of the isolation, that one goes through in science; some of the attempts that I’ve made to convince people to think about things differently and how little progress I felt I’d made in some of the changes that I’d been trying to advance for some time now. And I think that that’s a pretty common experience across many of my colleagues that are underrepresented in the sciences.

Céline Gounder: Apart from being uncomfortable, the lack of diversity in science actually stands in the way of the scientific process.

Kafui Dzirasa: One of the key things here is for scientists to both observe and appreciate the bias that comes along with being a human being. In terms of the scientific field, appreciating that there’s harm that comes along with that bias, but also, more broadly, making the case that science is, in and of itself, harmed when scientists don’t take into account the bias that comes along with inherently being a human.

Céline Gounder: Harold and Kaf think financial incentives and government support will help bring about a new, more diverse generation of scientists.

Harold Varmus: The biggest part of this is going to be, to try to make people of color who are, who are interested in pursuing scientific careers, make it possible for them to engage in the long training program that’s required and without falling into the kind of debt that’s just inhibitory to to entering these careers. That will take quite a lot of money. We also were interested in trying to provide more support for research grants that are again, expensive. $300,000 a year, for example.

Céline Gounder: Kaf is preceded by trailblazers like David Satcher. And Kaf wants to pass on the baton. He hopes that with the work he’s doing now… that might… be possible.

Kafui Dzirasa: Now I’m really hopeful that in this moment, transformation will come.

CREDITS

AMERICAN DIAGNOSIS is brought to you by Just Human Productions. We’re funded in part by listeners like you. We’re powered and distributed by Simplecast.

Today’s episode was produced by Zach Dyer, Temitayo Fagbenle, and me. Our theme music is by Allan Vest. Additional music by The Blue Dot Sessions.

If you enjoy the show, please tell a friend about it today. And if you haven’t already done so, leave us a review on Apple Podcasts. It helps more people find out about the show!

Follow AMERICAN DIAGNOSIS on Twitter and Just Human Productions on Instagram to learn more about the characters and big ideas you hear on the podcast.

We love providing this and our other podcasts to the public for free… but producing a podcast costs money… and we’ve got to pay our staff! So please make a donation to help us keep this going. Just Human Productions is a 501(c)(3) non-profit organization, so your donations to support our podcasts are tax-deductible. Go to AMERICANDIAGNOSIS.fm to make a donation. That’s AMERICANDIAGNOSIS.fm.

And if you like the storytelling you hear on AMERICAN DIAGNOSIS, check out our sister podcast, EPIDEMIC. On EPIDEMIC, we cover the science, public health, and social impacts of the coronavirus pandemic.

I’m Dr. Celine Gounder. Thanks for listening to AMERICAN DIAGNOSIS.