S3E10 / This Nonviolent Stuff’ll Get You Killed / Akinyele Umoja, Fletcher Anderson

The Civil Rights Movement is famous for its nonviolent tactics, but was it really nonviolent? What role did guns play? Can you have a nonviolent movement and still be armed?

Note: This season of American Diagnosis was originally published under the title In Sickness & In Health.

This podcast was created by Just Human Productions. We’re powered and distributed by Simplecast. We’re supported, in part, by listeners like you.

Charles E. Cobb: That’s what got Medgar Evers killed. That’s what got Martin Luther King killed. That’s what got any number of less prominent black people killed.

Akinyele Umoja: They weren’t going to get protection from the police.

Cynthia Anderson: If you don’t defend yourself, who you think will?

Celine Gounder: Welcome back to “In Sickness and in Health,: a podcast about health and social justice. I’m Dr. Celine Gounder. This season we’re looking at gun violence in America. The civil rights movement is famous for its nonviolent tactics. Sit-ins at lunch counters, riding integrated buses into the Jim Crow south, marches for hundreds of miles to raise awareness about voting rights. But not many people know how important guns were to the civil rights movement. In today’s show, we’re going to look at the role guns played alongside nonviolent civil disobedience during the struggle for civil rights. And we’ll ask: can you have a nonviolent movement and still be armed? Charles E. Cobb is a journalist and civil rights activist. He was a field secretary for the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee… SNCC for short.

Charles E. Cobb: Between 1962 and 1967 a very violent period.

Celine Gounder: Charles wrote a book about those years called, This Nonviolent Stuff’ll Get You Killed. As a young man volunteering to register voters in the South, Charles said that black veterans were critically important to the success of groups like SNCC and the Congress for Racial Equality, CORE.

Charles E. Cobb: Certainly for us as young people in the 1960s, the key adults, the key adult males for us, the ones who guided us in Mississippi, Georgia, and Alabama were World War II veterans. Many of them local NAACP leaders.

Celine Gounder: African Americans who served abroad came away from the experience profoundly changed.

Charles E. Cobb: These black veterans that we encountered in Mississippi in the 1960s, were constantly telling us stories about what they encountered when they were overseas in the South Pacific or in Europe. It was not the world that they had learned to accept in the United States.

Celine Gounder: This was happening as early as World War I, when black intellectuals like W. E. B. DuBois were encouraging African Americans to serve as a way to gain more rights.

“And with Pershing in France, Jim wasn’t there, but his sons were serving with the 801 pioneer regiment…”

Celine Gounder: This is audio from U. S. War Department propaganda. It was a film to encourage African Americans to enlist. By the time the United States entered World War I in 1917, the French were desperate for soldiers. So when the U.S. forces showed up, they put the African American servicemen to work and fight right alongside French troops.

”…fighting alongside the 8th Illinois on the soixante front…”

“The first to receive the croix de guerre…many received honored medals.”

Charles E. Cobb: So Pershing asked the French to issue a memorandum on how to treat black people.

Celine Gounder: General John Pershing, the commander of American forces during WWI, was disturbed by the equal treatment of African American soldiers by the French.

Charles E. Cobb: Here it is. It was on August 7, 1918 memorandum called “secret information concerning black American troops” … the document stresses that French officials needed to understand the sensitivities of race in America and recognize that Black people would pose a dire threat once they returned home unless they were consistently separated from Whites while overseas. … Quote, “The vices of the negro are a constant menace to the American who has to repress them sternly,” end quote.

Celine Gounder: The French tore up the memo.

“When they cleaned up in France, the boys came marching home…”

Celine Gounder: The First and Second World Wars were the first time these African American servicemen had seen a life outside the Jim Crow south. And it made an impression.

Charles E. Cobb: What black leaders, in particular the black community in general, was picking up on is the rhetoric of freedom and democracy that was les westwrapped around the rhetoric of struggle against Adolf Hitler in Europe… Furthermore, they came back home with their guns… the Ku Klux Klan and the likes, were increasingly discovering in the aftermath of World War II that the people they came to shoot were increasingly inclined to shoot back.

Celine Gounder: In our last episode, we talked about white supremacist terrorism like lynchings after the Civil War. But 1954 set off a whole new wave of attacks by the KKK and other hate groups. The reason? Brown v. the Board of Education. This decision struck down the Jim Crow mainstay of “separate but equal” in education.

Celine Gounder: Now why did the Supreme Court’s Brown decision trigger an expansion of the KKK and more anti-black violence?

Charles E. Cobb: Social inequality was high up on the list of white nightmares, and little black boys going to school, perhaps sitting on one desk over from little white girls was simply seen as intolerable. That’s all. Social equality. The term doesn’t exist today, but back then, it was rallying quiet cries for white terrorism.

Celine Gounder: In1955, Rosa Parks refused to give up her seat on a bus in Montgomery, Alabama. 14-year-old Emmett Till was lynched. And Dr. Martin Luther King. Jr’s home was bombed in 1956. Charles E. Cobb was getting ready to go off to college when the sit-ins started in the 1960s. He saw news about nonviolent civil disobedience. Guns had never been in Charles’s life growing up in Washington, D.C. or Springfield, Massachusetts. But when he stayed with families in Mississippi as an organizer, they were everywhere.

Celine Gounder: There was a CORE volunteer freedom house. Did their practice of nonviolence make them sitting ducks, and who protected the house?

Charles E. Cobb: There were people in the community that kept an eye out. All these communities, people… that’s what the missed point about southern movement is how embedded the civil rights workers were with the community. That’s who kept an eye out. Civil rights workers didn’t have to mount armed guards.

Celine Gounder: Older folks in the civil rights movement—the “grownups” as Charles called them—were more likely to carry guns for protection than the younger SNCC and CORE volunteers from out of state.

Charles E. Cobb: …we were staying with families when we were working in the south. Every household I ever stayed in had guns. It didn’t take me long to figure out that was a good thing they had guns. Helped keep me alive. Because what local people we were working with said, look, and they saw themselves as a part of a nonviolent movement, and they would tell you they are part of a nonviolent movement even as they were cleaning their rifles. Basically their attitude was, “Charlie, we’re not going to let these white people kill you,” and I was for that.

Celine Gounder: Leaders like Hartman Turnbow and Fannie Lou Hamer were famous for their guns. Charles met Fannie Lou Hamer when he was working for SNCC as a field coordinator in Mississippi.

Charles E. Cobb: Well, I was with Mrs. Hamer the first time she tried to register to vote.

Celine Gounder: That was in 1962. Fannie Lou Hamer lost her job and home as a result of trying to register to vote. She would become a powerful voice for civil rights. But her activism put her in the cross hairs of the KKK.

Charles E. Cobb: Mrs. Hamer had shotguns too. She told us at one point, although by no stretch of imagination was Mrs. Hamer inclined to organize an army or anything like that, but she did say, and I can quote her exactly, she said, “I keep a shotgun in every corner of my bedroom, and the first cracker tries to throw some dynamite on my front porch won’t write his mama again.”

Celine Gounder: Hartman Turnbow was another Mississippi civil rights activist who had reservations about nonviolence in the face of terrorism.

Charles E. Cobb: Well, Martin Luther King was touring Mississippi. This is in 1964 and he was going right across the state and he’s being introduced to local leaders and one of the local leaders we worked with was Hartman Turnbow, a small farmer in Holmes County, Mississippi. … Mr. Turnbow, always heavily armed and never known to be shy about speaking his mind, after the courtesies of introduction looked at Reverend King and said, I quote him exactly, he goes, “Reverend King, this nonviolent stuff ain’t no good. It’ll get you killed.” Unfortunately, he was right, in the sense that King ultimately is assassinated, of course…

Celine Gounder: The role of guns divided the civil rights movement. For organizers like Charles E. Cobb, nonviolence was an effective tactic, but it was never an end in itself. Other leaders like John Lewis were committed to nonviolence as a way of life, Charles said. They believed that there was good in all people and through your actions you could change someone’s mind.

Charles E. Cobb: That’s a deep philosophical approach to life, and they studied it. … We didn’t have anything like that. For us, what we studied were tactics. If you are attacked by a mob, how do you protect yourself from serious physical harm? How do you protect somebody else who is under assault? How do you use your body to do that? Those are trainings in the tactics of non-retaliation, if you will, but they’re not rooted really in a philosophical concept. …when I first see the sit-ins erupt in 1960 I understand nonviolence as a movement to be a movement of non-violent direct action. I saw that as a tactic and the question for me as getting ready to go off to college when the sit-ins broke out in 1960, was could I really do that? That did not hang on a philosophical debate about nonviolence. It was, “can I really let white people beat up on me like that?”

Celine Gounder: So, could you participate in nonviolent protest but still be armed? That question was front and center in the summer of 1966 during the March Against Fear.

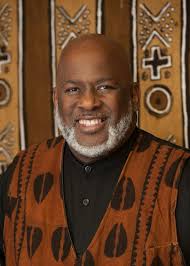

Akinyele Umoja: Oh, man the March Against Fear started by one lone black man, James Meredith.

Celine Gounder: This is Akinyele Umoja. He’s an activist and Chair of African American studies at Georgia State University. James Meredith was the first African American man to attend the University of Mississippi Law School. After the 1965 Voting Rights Act became law, James decided to go on a march from Memphis to Jackson, Mississippi to prove there was nothing for black Americans to fear in voting.

Akinyele Umoja: He went on the march, and early in the march, while he’s entering the state of Mississippi, in northern Mississippi he’s shot by a sniper. Fortunately he survives the sniper attack, but the civil rights movement was concerned. … There’s a debate amongst the leaders because the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee and CORE, they wanted to have the Deacons for Defense provide security.

Celine Gounder: The Deacons for Defense and Justice was an armed, black self-defense group. After the police escorted a KKK march through a black neighborhood in Jonesborough, Mississippi in 1964, a group of black men and women—including some veterans, started patrolling their neighborhoods with guns.

Fletcher Anderson: We were very good at what we did.

Celine Gounder: Fletcher Anderson was a founding member of the Deacons for Defense chapter in Bogalusa, Louisiana who helped patrol the march that summer. He told his story to the American Folklife Center at the Library of Congress as part of a project documenting the civil rights struggle.

Fletcher Anderson: We were very good at what we did. We protected our neighborhoods. That stopped people from driving by, shooting up in their houses and beating them. We had walkie-talkies. We had things that communicate with one another all through the community. We’d know where everybody was at. We’d know if – we had block captains. We had everything set where anything – if anybody come in there, we were able to block the streets off. Because we have to be – we had to be our own protection, because the police were not there to protect us.

Joseph Mosnier: Exactly.

Fletcher Anderson: They were there to protect the Ku Klux Klan.

Celine Gounder: The interviewer, Joseph Mosnier, asked Fletcher Anderson’s wife, Cynthia, what people in Bogalusa thought of her husband joining the Deacons for Defense. Cynthia is white.

Cynthia Anderson: All of the advice that other people gave me: “Leave him! You’re just going to get yourself killed and get your children killed.” No, that’s not my way. I believed in what they believed in. If you don’t defend yourself, who do you think will?

Celine Gounder: Civil rights organizers were divided over the role of a black militia like the Deacons participating in the march.

Akinyele Umoja: The NAACP’s Roy Wilkins and Whitney Young of the Urban League didn’t agree with that, and Dr. King said he could agree to the Deacons being near to patrol the march, but they could lead it, and they could be behind it, but they didn’t want anyone in the march to carry guns. That was the compromise they struck, and NAACP and Urban League decided couldn’t get with that. They left.

Celine Gounder: The March Against Fear reached Jackson, Mississippi without another violent incident. But the split between the NAACP and groups like SNCC over armed self-defense groups like the Deacons led to a more in-your-face approach to self defense by black activists. This was the summer of Black Power.

Akinyele Umoja: The slogan of Black Power becomes another thing that’s popularized out of the march. You register thousands of voters. You have the Deacons for Defense and the media picks that up to. The movement which was exclusively not at least they thought was exclusively nonviolent. Prior to that you got you had these black people with guns, rifles and shotguns and handguns and walkie-talkies patrolling the march and protecting the marchers. The media picks up there’s something different going on and that’s part of this black power movement that inspires groups like the Black Panther Party and other organizations all across the United States.

Celine Gounder: The summer of 1966 inspired Huey Newton and Bobby Seale to form the Black Panther Party for Self-Defense in Oakland, California.

Akinyele Umoja: They figured out what was the legal distance you could stay away to observe police officers. They decided, inspired by the Deacons, that they were going to do armed patrols of police because they just thought police harassment and police brutality had gotten out of control.

Celine Gounder: These armed patrols caught the attention of the country. Believe it or not, California of all places had lax gun laws. It was legal to carry loaded pistols, shotguns, any kind of gun, in public. As long as the Black Panthers kept their distance from the police they could follow them and observe arrests and patrols.

Celine Gounder: The Black Panther patrols sent shivers down the spine of the political establishment in California. Republican Assemblyman Don Mulford drafted a bill to repeal the state’s law that allowed carrying of loaded firearms in public.

“The Black Panther Party calls on the American people to take careful note of the racist California legislature considers legislation to keep black people disarmed while racist police agencies throughout the country intensify the harassment of black people.”

Celine Gounder: The 1967, a group of roughly 30 Black Panthers took their guns to the California statehouse in protest.

“Am I under arrest? Am I under arrest?”

Celine Gounder:The police tried to disarm the Black Panthers when they entered the statehouse. Several Black Panther demonstrators were arrested. Huey Newton, one of the founders of the Black Panthers, told reporters they had every right to be there:

“They put trumped up charges on people who exercised their constitutional right and said they had no right to bear arms in a public place. The Second Amendment protects the citizens’ right to bear arms on public property.”

Celine Gounder: California’s governor at the time, Ronald Reagan, signed the Mulford Act later that year.

Akinyele Umoja: When they passed that law, that’s what prevents armed patrols. In fact that’s one of the things that the Panthers are known for, but they only had a policy—it was less than a year that they openly carried weapons out there in the streets like that.

Celine Gounder: There were other attempts to disarm black nationalist groups like the Black Panthers or self-defense militias like the Deacons for Defense. But Akinyele says that the most effective tool for disarming these black self-defense forces wasn’t laws or law enforcement. It was the civil rights victories—locally or nationally—that made African Americans feel safer.

Akinyele Umoja: What actually disarmed the Deacons was when they started to make civil rights gains. For instance, Claiborne County, I went there, and some of the Deacons were now working for the sheriff’s department. You had black people who had become part of the police departments… They didn’t feel the same need to have a Deacons for Defense Organization when they were a part of law enforcement. And so that’s what actually stops it.

Celine Gounder: Now, was armed black resistance successful in repelling white supremacist violence?

Akinyele Umoja: Yes, most definitely, most definitely. … Not always successful, but many times they were successful at protecting and defending themselves…

Celine Gounder: Fletcher Anderson, the member of the Bogalusa chapter of the Deacons for Defense, agrees.

Joseph Mosnier: Um, when you think back on the Bogalusa movement, could it ever have taken the form that it did without the real capacity in the community for self-defense?

Fletcher Anderson: I don’t think so.

Cynthia Anderson: Me either.

Fletcher Anderson: I don’t think so. Because we have to be able to – for the community to see that there was somebody going to protect them, that they could go to bed, knowing that somebody was out there protecting them, that they wasn’t going to be drug out of their houses, they wasn’t going to be killed, their children wasn’t going to be an Emmett Till or those type situations happening to them. And once they knew that, they was able to come out and go to their jobs and come back. A lot of them suffered. A lot of them got laid off. … And they suffered, too. They suffered, too. But without the Deacons of Defense, your question, no, it couldn’t have stood. … The fear is gone out of black people of the Ku Klux Klan. That fear is gone. There is no more fear there. The Deacons took the fear out of it… But it also shows you that you don’t look for trouble; all you do is protect yourself. Protect yourself. Yeah. And so far that been happening here.

Celine Gounder: It’s impossible to deny that guns played an important role in the struggle for civil rights. Military service during World War I and II showed black men that they didn’t have to accept the status quo. They enlisted to fight fascism overseas… and returned home… to become civil rights leaders… fighting America’s own brand of fascism: white supremacy. The civil rights movement was nonviolent… in that violence was not used to achieve racial justice. Guns weren’t tools of aggression… bitterness… or vengeance. They were tools of self-defense. Nonviolence was a key tactic… because many whites… even those sympathetic to the civil rights cause… were terrified of black vengeance… of having to atone for wrongs past and present. It’s why many today are insistent that the oppressions of slavery and racism are in the past… that we live in a post-racial, color-blind America. It’s why many find the Black Lives Matter movement so unsettling.

Celine Gounder: Next time, we’ll speak with African American gun and gun safety advocates to see what armed self-defense looks like for black Americans today.

Celine Gounder: Today’s episode of “In Sickness and in Health” was produced by Zach Dyer and me. Our theme music is by Allan Vest. Additional music by The Blue Dot Sessions. Audio of oral history interviews with Cynthia Baker Anderson and Fletcher Anderson conducted by Joseph Mosnier care of the Civil Rights History Project Collection at the Library of Congress American Folklife Center.

Celine Gounder: You can learn more about this podcast and how to engage with us on social media at insicknessandinhealthpodcast.com. That’s insicknessandinhealthpodcast.com. If you like what you hear, please leave us a review on Apple Podcasts. It helps more people find out about the show!

Celine Gounder: I’m Dr. Celine Gounder. This is “In Sickness and in Health.”

Guests

Fletcher Anderson

Fletcher Anderson