S1E39: Invisible Women / Ai-jen Poo, Susie Rivera, Glewna Joseph

“Now that we see them, my hope is that our field of vision about who is working, and just how valuable they are, continues to widen. And that is it’s not only about awareness and clapping for them at seven o’clock at night, but we’re actively taking action and demanding that they be protected. Demanding that they be compensated. Demanding that they are able to keep their themselves and their families safe, crisis, or no crisis. “ – Ai-jen Poo, Director of the National Domestic Workers Alliance The workforce of domestic employees is comprised largely of women and women of color.

This group has been severely impacted by COVID-19, facing job insecurity, lack of paid sick days, and low wages. The pandemic relief bills passed by the Senate for essential workers had conspicuously excluded domestic workers, leaving them vulnerable to disruptions caused by the pandemic. In today’s episode, we hear from Ai-jen Poo, the Director of the National Domestic Workers Alliance; Susie Rivera, a home caregiver in Texas; and Glewna Joseph, a housekeeper. We discuss the ways in which their work has been changed by COVID-19, how the pandemic has brought awareness to the need for increased protection of domestic workers’ rights, as well as the steps being taken to bring about these much-needed changes.

This podcast was created by Just Human Productions. We’re powered and distributed by Simplecast. We’re supported, in part, by listeners like you.

Julie Levey: Hi, I’m Julie Levey. I’m an intern working with Just Human Productions on “Epidemic.” Nominations for the 2020 People’s Choice Podcast Awards are open until July 31st. To show your support, please go to podcastawards.com and nominate us in the People’s Choice and Health categories. That’s podcastawards.com. Thank you!

Celine Gounder: This is “Epidemic.” I’m Dr. Celine Gounder. Today is Tuesday, July 28th.

When the Senate first passed pandemic relief bills for essential workers, one group was conspicuously left out.

Ai-Jen Poo: The workforce of mostly women and mostly women of color who provide caregiving and cleaning services in our homes, supporting our families, as nannies, as house cleaners, and as home care workers.

Celine Gounder: This is Ai-Jen Poo. As Director of the National Domestic Workers Alliance, she’s spent decades advocating for this often-overlooked and undervalued segment of the American workforce. Now, the pandemic is creating a rare opportunity.

Ai-Jen Poo: So much gets revealed in a crisis. We’ve become so aware of just how many invisible workers are actually essential to our lives.

Celine Gounder: And her organization is hoping to capitalize on that awareness.

Ai-Jen Poo: Now that we see them, my hope is that our field of vision about who is working and just how valuable they are continues to widen. And that is it’s not only about awareness and clapping for them at seven o’clock at night, but we’re actively taking action and demanding that they be protected. Demanding that they be compensated. Demanding that they are able to keep themselves and their families safe, crisis or no crisis.

Celine Gounder: This week on “Epidemic,” we’re going to hear about that action. But first, we spoke with some of the women the National Domestic Workers Alliance is working to protect. Susie Rivera has worked as a caregiver in Texas since 1986.

Susie Rivera: Prior to this pandemic, I was working a lot. I was working like between a hundred and 110 hours a week. And now I’m only taking care of two patients.

Celine Gounder: One of those patients is a woman who recently survived a stroke.

Susie Rivera: The family was fearful of her catching coronavirus. So her family did not want to leave her in a nursing home. Her family didn’t want to leave her in rehab. They wanted to find 24-hour care in her home.

Celine Gounder: And so, they hired Susie.

Susie Rivera: I work Monday, Tuesday, and Wednesday. I work 16 hours a day. I go in at 6:00 and get off at 10:00, and she’s really depending on me for all her care, and it’s total, total care.

Celine Gounder: The stroke left the woman with limited mobility.

Susie Rivera: I assist her in her medications. She then gets up, she gets a shower. I help her brush her teeth. I comb her hair, put rollers on her hair, put makeup on her. Then she gets transferred to her recliner. I give her her breakfast. Then I give her her eight o’clock medications.

Celine Gounder: Susie lifts her patient at least twenty times each day, moving her from her bed, to her wheelchair, back to her bed for a nap. Susie preps her meals, answers her phone, washes her laundry, cleans the house, too.

Susie Rivera: And she just needs a lot of one-on-one total care.

Celine Gounder: Susie considers this work a calling.

Susie Rivera: You are an essential part of that family’s life, of their mother or father living the quality of life they have at the end of their life, and you want them to get the care that you would give your mother or your father, your own family member.

Celine Gounder: In her twenty-eight years in this industry, she’s done all sorts of work.

Susie Rivera: I’ve taken care of all kinds of people at different points of their life. I’ve done end-of-life care. I’ve done hospice, I’ve worked in nursing homes.

Celine Gounder: But she’s never experienced anything like this.

Susie Rivera: This has been the most stressful, stressful of all times of me working. It’s just draining me. And I was used to the long hours and the work we put in, but it’s just so much stress right now, making sure they’re safe, making sure they have equipment, making sure they have gloves or even hand sanitizers or, or masks. This is really a total, a total change from work I’ve done before.

Celine Gounder: Her patient’s family is supplying Susie with appropriate protective equipment, and she wears it to protect her patient. But also…

Susie Rivera: I’m really fearful because my wife has compromised illnesses.

Celine Gounder: Her wife’s sister and two nieces are living with them right now, too, and Susie is trying to keep everyone safe. Then there’s her parents, who she tries to convince to stay home.

Susie Rivera: It takes a toll on you because you want to care for people, and it’s just so stressful, so stressful.

Celine Gounder: For millions of others, the pandemic creates a different kind of stress.

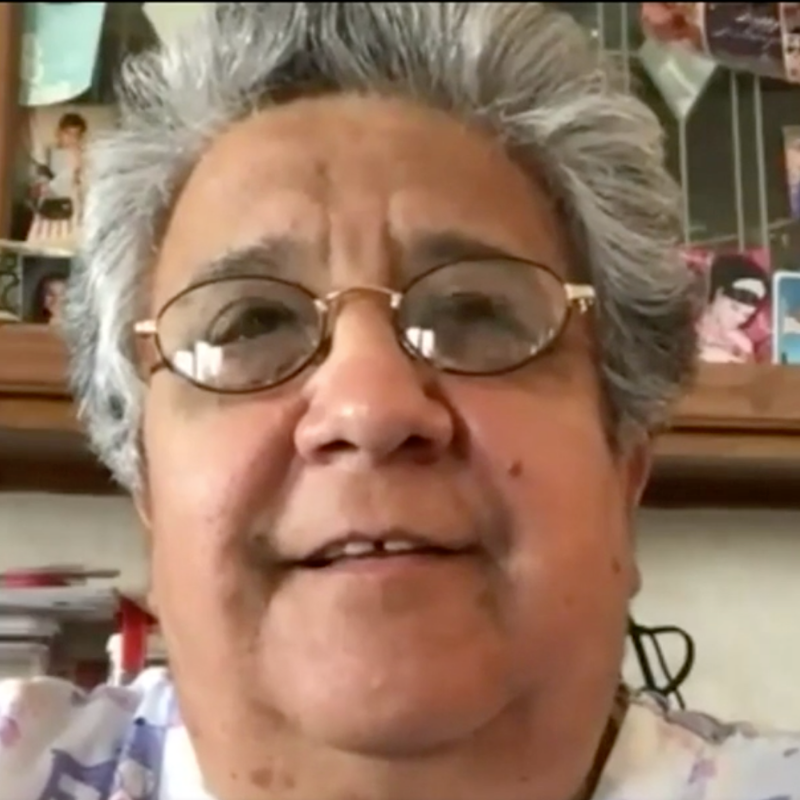

Glewna Joseph: My name is Glewna Joseph and I am a housekeeper.

Celine Gounder: Back in 2014, Glewna had just been happy to find a job. She’d immigrated to the U.S. after a difficult divorce, leaving behind a career as an accountant. Her accounting license didn’t transfer to the United States and friends helped her find housekeeping work.

Glewna Joseph: I was working for a billionaire.

Celine Gounder: If you didn’t catch that, she said she was working for a billionaire, with a “b.” As a live-in housekeeper, she’d work five days per week, starting at 10:00 in the morning. The first week, her days ended around 6:30 p.m. But that didn’t last long.

Glewna Joseph: As time went by, a lot of things changed.

Celine Gounder: Two months in, the employer asked Glewna if she’d like to come to the Hamptons with them for the summer. Again, Glewna agreed. On the drive out, more news.

Glewna Joseph: Don’t forget that your schedule changes at the end of June.

Celine Gounder: She’d now be working weekends. The Hamptons house was twice the size of the other house. And there were people in and out all summer, plus weekly parties. Most nights didn’t end until 11:00, or 11:30 at night. Despite the extended hours, the pay remained the same. $600 per week.

Glewna Joseph: There’s no overtime.

Celine Gounder: Other things changed, too.

Glewna Joseph: But by the third to the fourth year, when they started to travel, I had to go clean the grandmother’s house. I had to go clean the daughter’s house. I had to, when the fiance was moving out, I had to go help clean that house. So I find myself constantly taking care of so many different households. And my compensation was, “Thank you, Glewna. I appreciate you.”

Celine Gounder: When she joined the National Domestic Workers Alliance, she started to see all of the ways her employers were taking advantage of her, and how much better things could be with a fair employer. And so, she quit. She’s been out of work since January. But in March she felt like that was going to change. She was finalizing details for a new job. And then… the pandemic hit New York. Hard.

Glewna Joseph: Everything just went on a stand still. So the job that was promised, went down to drain, and that was it for me.

Celine Gounder: She’s still looking…

Glewna Joseph: I am looking into housekeeping, into nannying, but it’s tough, it’s tough. And the competition is so high, because so many people are unemployed right now that it makes it even more difficult to find employment.

Celine Gounder: She’s burned through her savings and is now getting by with the support of friends and a local food bank. Her son helps with some bills, too. Still…

Glewna Joseph: I’m not sure how long I could continue doing this because July is almost coming to an end and I’m not sure what’s going to happen, so I’m just praying that something happens and my landlord to be as patient as possible with me. So it’s rough, it’s tough.

Celine Gounder: Glewna has also received support from the National Domestic Workers Alliance. That’s the organization that Ai-Jen leads. In March, they established a Coronavirus Care Fund.

Ai-Jen Poo: To provide emergency cash assistance to domestic workers in need who’ve been affected during the pandemic because we were hearing over and over again, that there was no other relief coming.

Celine Gounder: There are more than 2.5 million domestic workers in the U.S.—actually some estimate it’s closer to 4.5 million—and the National Domestic Workers Alliance understood that this community would need relief as much, if not more than, most others. And most, like Glewna and Susie, are trying to manage it all with less income.

Susie Rivera: A lot of us have multiple jobs.

Celine Gounder: That’s in normal times…

Susie Rivera: Just to get what you need, your insurance, your medication if you take it, you know, because medication is expensive, too.

Celine Gounder: There’s internet, cell phones, rent, utilities, grocery bills. In her last job, Glewna made $34,320 per year. That’s assuming she worked every week of the year, that she never took a holiday, that she never got sick.

Ai-Jen Poo: So many women work incredibly hard and still cannot make ends meet. The average annual income of a home care worker is $16,000 per year. One-six. Sixteen thousand dollars per year.

Celine Gounder: And now, it’s worse.

Ai-Jen Poo: This pandemic has been devastating, nothing short of devastating. It is a crisis of impossible choices. Early on in the crisis, we started to hear about people worrying. If they got sick, what would they do? And then we started to hear about dramatic losses in jobs and income; house cleaners were some of the first people in February to tell us that they were losing clients and losing income and worried about food security for their families.

Susie Rivera: And some are, some workers are even fearful because the family is not taking precautionary measures. They don’t want to go in the house because they’re having family come in, a lot of exposure. A lot of people are coming and going in the house. That puts the worker at risk.

Celine Gounder: And if a worker has two jobs, one where the employer follows strict rules, and another where the employer shirks the rules… they can’t keep both jobs.

Susie Rivera: You can’t go to a house if you know they’re not abiding by the rules.

Celine Gounder: The crisis of impossible choices. But for some, there really is no choice.

Susie Rivera: You don’t work, you don’t get paid. That’s the bottom line.

Celine Gounder: No matter how hard some workers tried to avoid it, however, encountering the virus seemed to become inevitable. Many fell ill. And when they did, they faced yet another impossible choice.

Glewna Joseph: Alot of them fell sick and stayed at home and tried to use different remedies to, you know, to try and get better because of course, a lot of them are undocumented and they are afraid to go out there to get, to seek medical attention because they are afraid if they go out there, you’re afraid of ICE. They’re afraid that, you know, you’re going to put themselves and the family at risk.

Celine Gounder: And many never recovered.

Glewna Joseph: Some died on the job, some died at home. They caught the virus and then passed away.

Ai-Jen Poo: This is a workforce that came into the crisis without job security, without any kind of access to a safety net, without paid sick days or paid family leave. And the wages are poverty wages. So there’s not savings to stock up on groceries even.

Celine Gounder: And there was no help in sight.

Ai-Jen Poo: There’s no access to testing, there’s no access to protective equipment, and there’s no access to care should you get sick.

Celine Gounder: And while some qualify for unemployment, the majority do not.

Ai-Jen Poo: The undocumented workforce has not been eligible for any of the federal relief, and many are not able to certainly not able to get access to unemployment insurance. Many are not even showing up in the unemployment numbers and really the only safety net they have is the community and their networks, including organizations like ours.

Celine Gounder: And in Ai-Jen’s experience, this is not at all surprising.

Ai-Jen Poo: The fact that it has been work that has always been associated with women, right? Caregiving work has always been associated with women and as a profession associated with black women and immigrant women, it has really fed into and been a part of the ways in which our economy is structured to value the lives and the contributions of some over others.

Celine Gounder: She points to history, to the 1930s, when southern congressmen refused to support New Deal reforms and labor laws that included farm workers and domestic workers—work that, even then, was primarily done by people of color.

Ai-Jen Poo: And that legacy of racial exclusion has really shaped conditions of this work for generations.

Celine Gounder: It was clear that things needed to change, even before the pandemic.

Ai-Jen Poo: These are really the jobs of the future. If you think about just how many people need care work and care support in their homes and then you add on top of that the fact that people are living longer than ever and the Baby Boom generation, this huge defining generation of ours, is, is aging at a rate of 10,000 people per day turning seventy, we need a really strong and large workforce of care workers to provide support to that growing older population.

Celine Gounder: Experts say the U.S. will need more than 8 million new long-term care workers by the year 2028.

Ai-Jen Poo: It’s one of the reasons that we’ve been working so hard for so many years to help domestic workers get access to a safety net.

Celine Gounder: The National Domestic Workers Alliance created an online platform to help domestic workers negotiate benefits with employers. The website is MyAlia.org—that’s A-L-I-A. They’ve also championed Domestic Workers’ Bills of Rights. New York was the first to adopt one, signed ten years ago. It offered all domestic workers—regardless of their immigration status—several basic rights.

Ai-Jen Poo: Three paid days off per year as well as some basic protections from discrimination and harrassment, the right to a day of rest per week.

Celine Gounder: It provides disability pay, overtime pay, and protection under the New York State Human Rights Law.

Ai-Jen Poo: Nothing revolutionary, but it was really important especially as a step forward to say domestic workers are workers and are protected and have rights equal to other workers.

Celine Gounder: Six states and several cities have since signed similar bills. A federal version is currently on the Senate floor. The original bill came to Glewna’s attention in 2018, when she joined the alliance.

Glewna Joseph: This is where I learned what my rights were. I was given a contract, and I was told, “Take this contract to your employer.” And I looked at the contract and I said, “If I take this contract to my employer, I would get fired immediately,” because she has violated 80% of what’s on that contract.

Celine Gounder: She knew what she wanted to find in her next job. She would no longer live in an employer’s home. And she’d negotiate a few other things…

Glewna Joseph: I would negotiate for sick days. I would negotiate for holiday, holiday pay. I would have negotiated for them to pay health insurance for me. So I would negotiate for the, for the same time out, because for me, as far as I’m concerned as employers, they get those benefits on their jobs. So I think it’s only fair that I may come into your home to take care of your home, whether it’s your baby or your house, as an employee, I deserve the very same thing. So I would negotiate for that.

Celine Gounder: She’d be negotiating for many of the things that one of Susie’s employers has started to offer.

Susie Rivera: There’s another lady that I take care of on Thursday, Friday and Saturday. She is a very wealthy lady, and she takes care of her employees very good. She runs her care like a business. We have sick days, vacation days. She pays for our medical, but that’s an ideal job. Nobody the whole time I’ve done this kind of work has ever done this for me or for any worker. And I really feel this lady who does all this for us, she really appreciates us, and she knows how hard we work.

Celine Gounder: And thanks to the pandemic, that awareness is spreading.

Ai-Jen Poo: We are all caregivers now. I mean, with our kids home from school and daycare and camps closed for the summer and parents getting evacuated from nursing homes, we are all trying to figure out how to manage care for our families while some of us are able to work at home. Some of us are trying to figure out how we find work again, it’s so much, and I think it’s really awakened us to this part of our lives that we have really not paid enough attention to and not invested in.

Celine Gounder: And in Ai-Jen’s opinion, now is the perfect time to create lasting change.

Ai-Jen Poo: If we made every care job in America a living wage job with benefits, it would not only get a whole set of people to work immediately. Those jobs are job-enabling jobs. They make it possible for all of us to go and figure out how we get back to work again, as a country, knowing that our loved ones have care and are in good hands and what could be more fundamental and what could be a better stimulus than that, really, and so that’s what we’re advocating for. Now we just have to jump through that window and make it happen.

Celine Gounder: “Epidemic” is brought to you by Just Human Productions. We’re funded in part by listeners like you. We’re powered and distributed by Simplecast.

Today’s episode was produced by Zach Dyer, Danielle Elliot, and me. Our music is by the Blue Dot Sessions. Our interns are Sonya Bharadwa, Annabel Chen, and Julie Levey.

If you enjoy the show, please tell a friend about it today. And if you haven’t already done so, leave us a review on Apple Podcasts. It helps more people find out about the show!

You can learn more about this podcast, how to engage with us on social media, and how to support the podcast at epidemic.fm. That’s epidemic.fm. Just Human Productions is a 501(c)(3) non-profit organization, so your donations to support our podcasts are tax-deductible. Go to epidemic.fm to make a donation. We release “Epidemic” twice a week on Tuesdays and Fridays. But producing a podcast costs money… we’ve got to pay our staff! So please make a donation to help us keep this going.

And check out our sister podcast “American Diagnosis.” You can find it wherever you listen to podcasts or at americandiagnosis.fm. On “American Diagnosis,” we cover some of the biggest public health challenges affecting the nation today. In Season 1, we covered youth and mental health; in season 2, the opioid overdose crisis; and in season 3, gun violence in America.

I’m Dr. Celine Gounder. Thanks for listening to “Epidemic.”