S1E50: The Post-Pandemic College Experience / Scott Galloway & Michael D. Smith

“There’s this toxic cocktail of low endowment per student, high tuition, low experience, low certification… Those universities could be out of business in a year.” – Scott Galloway

Coronavirus concerns forced many universities to close their campuses this fall. The mix of fewer students on campus, canceled athletics, and online courses is threatening the viability of many traditional colleges and universities. But the pandemic is also creating opportunities to re-imagine what higher education could look like in the future. This first episode in our series on COVID’s impacts on the economy looks at why some schools are so vulnerable, the next big thing in online education, and how these schools can pivot in a post-pandemic market. This podcast was created by Just Human Productions. We’re powered and distributed by Simplecast. We’re supported, in part, by listeners like you.

Michael Smith: Our diplomas are no longer going to be as valuable as they’ve always been, because employers are going to have different signals, available to evaluate how smart and how well motivated students are.

Scott Galloway: There’s this toxic cocktail of low endowment per student, high tuition, low experience, low certification. Those universities could be out of business in a year.

Céline Gounder: Welcome back to EPIDEMIC, the podcast about the science, public health, and social impacts of the coronavirus pandemic. I’m your host, Dr. Céline Gounder.

OK, I’ve got to say, I love the movie Good Will Hunting.It takes me back to my residency days in Boston. In case you’ve never seen it, Matt Damon plays a young, self-taught math genius who works as a janitor at MIT.

Good Will Hunting: How you like them apples?Céline Gounder: I did my residency at Mass General and there was a bar just across the river that I used to go to in Cambridge. A famous scene from the movie was shot there. Matt Damon’s character, Will, stands up to a snobbish bully who tries to embarrass one of his friends.

Good Will Hunting: “You dropped $150k on a f***** degree you could have gotten for $1.50 in charges at the public library.”

“Yeah, but I will have a degree, and you’ll be serving my kids fries at a drive through on the way to a ski trip”

Michael Smith: Yeah, that scene is so crushing, right?

Céline Gounder: This is Michael Smith.

Michael Smith: Will Hunting has a world of talent, but he doesn’t have the money to demonstrate that talent to the, to the market. Will Hunting is not alone in our current world.

Céline Gounder: Michael is a Professor at Carnegie Mellon. His research focuses on technology and how it affects the way markets and industries work.

Michael Smith: Anytime you’ve got a talented person who can’t show their talent in the marketplace, that’s bad for them. And it’s bad for me and you too.

Céline Gounder: University education has gotten even more expensive since Good Will Huntingwas released in 1997.And diplomas — especially from elite schools — are a big leg up when it comes to high paying jobs and social mobility in the United States. But this system has been rocked by the pandemic.

For many students, their classes have moved online during the pandemic. And that is creating big problems for many colleges and universities. One of the first schools to take dramatic action was Ohio Wesleyan University. Reduced revenues from students staying home drove the university to eliminate 18 majors. Ohio Wesleyan previously announced it was cutting 44 non-faculty positions as part of a multi-million-dollar cost-cutting measure. And some colleges have already closed their doors. Many universities reopened this fall with a mix of in-person and online learning. But with coronavirus cases surging as we record this episode in November… it’s unclear how many schools will offer in-person classes this spring. But the pandemic is also creating new opportunities to re-imagine what higher education could look like. This episode is the first in a series looking at how the pandemic has disrupted different sectors of the economy.

Education startups and Big Tech have been eyeing traditional higher education for years. And the pandemic may be the shock that pushes these alternatives into the mainstream.

Michael Smith: What we’re missing is the ways that online education can actually deliver new sources of value for our customers. That’s where the threat’s going to come in.

Céline Gounder: And hit the reset button on higher education in the United States.

Scott Galloway: So I think there’s an opportunity to dramatically expand enrolments using small and big tech dramatically decreased costs back to where we were at the last half of the 20th century, where education was the primary vehicle for upward mobility.

Céline Gounder: Today on EPIDEMIC, how the coronavirus is disrupting higher education.

Before we get too far, let’s talk about what a student pays for when they go to college. Is it the coursework? The networking? The parties?

Scott Galloway: Well, all of that has tremendous value, but if you look at it economically, if you want to justify the return on investment you’re making, it’s mostly its first and foremost, that certification.

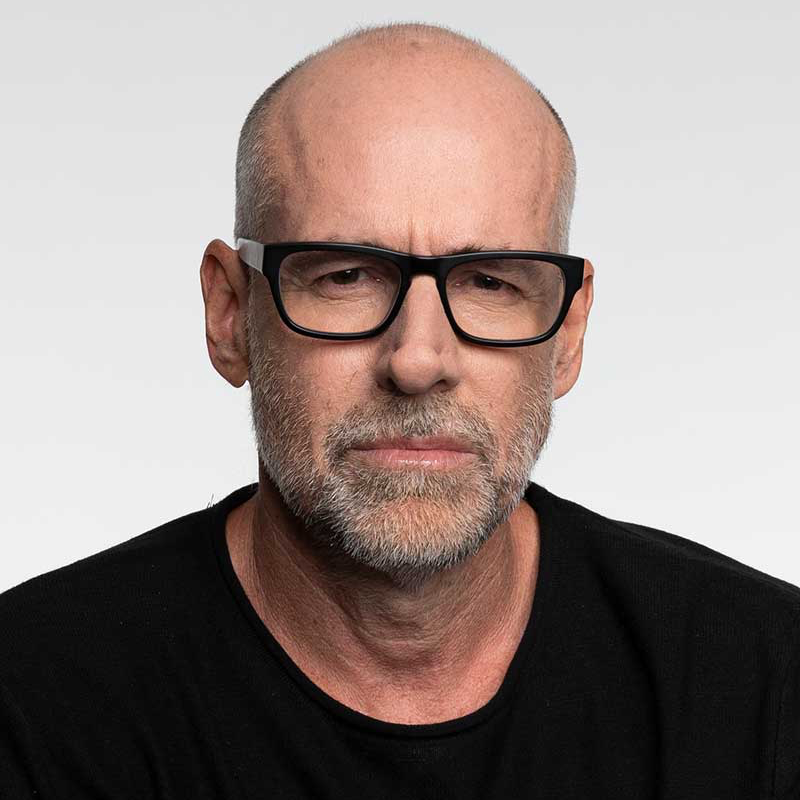

Céline Gounder: This is Scott Galloway. He’s a Professor of Marketing at the Stern School of Business at New York University.

Scott Galloway: I almost didn’t graduate from UCLA. I got a job at Morgan Stanley, and I had a fifth year, and I thought, you know, I’m not doing that well. I had terrible grades. I almost got kicked out, I almost left, but they wanted me to stay there one more semester, smoke a lot more dope, watch Planet of the Apesand other 300 times, and get that certification of a degree. Was I much better graduating three months later? No, but that certification, the corporations and a modern economy love is what is the real return on investment is.

Céline Gounder: A diploma is a signal to employers about who you are and how qualified you are. And getting that certification… especially from an elite school… makes the $150K that guy inGood Will Hunting paid look like a bargain. Incoming freshmen paying full-price tuition, room, and board at some elite universities today may end up paying nearly half a million dollars over four years.

Scott Galloway: It’s worth it. Because that Yale certification, that stamp on your forehead for the rest of your life, it says to the marketplace that you’re one of two things: you either freakishly remarkable the ages of 15 to 17, and be incredibly productive and corporations ranging from Google to McKinsey to the World Bank love those people; or your parents are rich and corporate America also loves rich kids. If you want to go into private wealth for Goldman Sachs, they love rich kids because it means that kids, parents have friends who are rich.

Céline Gounder: Scott says these institutions maintain the value of their diplomas through brand recognition and exclusivity.

Scott Galloway: People say Apple and Nike are the strongest brands in the world. No, they’re not. The strongest brands in the world are, you know, Harvard, MIT, Michigan, and Stanford. Nobody, nobody gives a $100 million to Apple to put their name on the side of a building on the Apple campus in Cupertino.

Céline Gounder: This system hummed along for decades until the pandemic.

Scott Galloway: My observation around COVID as it relates to our economy is that it’s more of an accelerant than a change agent. And there’s a lot of trends in place. Our tuition increases are unsustainable. Keeping admission rates low; a dependence upon international students who pay full freight to subsidize the cash flow of the university; exploding administrative costs; and just thought it just isn’t none of this is sustainable.

Céline Gounder: The immediate risk to a lot of these schools during the pandemic is financial.

Scott Galloway: If you’re a parent paying $58,000, just in tuition, maybe $80,000, including room and board, and your kids are going to be taken to zoom classes, you reevaluate the purchase.

Céline Gounder: This has already started. Northeastern University in Boston faced a class-action lawsuitfrom students after campuses closed and classes moved online last spring. Nearly a third of the student body at Kutztown University in Pennsylvania left campusin favor of remote learning because of COVID concerns.

Scott Galloway: When you have 10 or 20% fewer students, you go from having [00:25:00] $5 or $10 or $20 million to put in your endowment to losing $10, $20, $30 million, and you’re in a state of financial crisis. And a lot of these universities, if they can’t offer the dead poet’s society, leafy football, amazing adult-childcare experience, the people aren’t going to pay a Mercedes price for a Hyundai. I mean, the reckoning is coming.

Céline Gounder: And the reckoning won’t be evenly distributed. Scott thinks the top-tier schools — Ivy League institutions and flagship state schools, like the University of Michigan — will be fine in the long run. Scott says that community colleges will also do OK.

Scott Galloway: the community colleges are more resilient than you might think, Céline, because if you’re a Cal state, you have a half a million kids, you charged $7,000 and $17,000 for in state and out-of-state tuition, respectively, 83% of your students are commuters. So they’re paying a fairly reasonable cost. And they have never paid that money in exchange for this typical collegiate experience they’re paying for education and some certification out of low price. Their value proposition is largely intact or remains intact and an era of COVID.

Céline Gounder: The real trouble is going to be in what Scott calls tier 2 and tier 3 schools. Colleges that don’t have strong brand name recognition, whose students don’t graduate into well-paying jobs, but still charge tier 1 tuition.

Scott Galloway: Those universities could be out of business in a year.

Céline Gounder: And there’s something else besides the bottom line pressing down on transitional higher education during the pandemic, Big Tech.

Scott Galloway: I am confident one or more of them is going to go directly into the business of education/certification. If Google were to partner with the University of Washington or Berkeley and offer a two-year intensive programming, uh, curriculum, there’s a large job market for that.

Céline Gounder: Google’s former CEO Eric Schmidt has already announced plans to help the U.S. government create its own university certification program for AI and cybersecurity. Many tech giants are already looking elsewhere to find their top talent.

Michael Smith: So Google very publicly says that they’ve looked at their data and what they discovered is that the school you graduated from and the grades you got at that school, even, even the major, you had it at school, isn’t all that valuable for them when they try to predict whether you’re going to be a good Google employee. What is valuable to them is how well you do on their entrance exam.

Céline Gounder: Another example Michael gave was a website called Kaggle. Basically, it’s a crowdsourcing platform for very difficult data analytics problems. Companies, government agencies, and researchers post problems on the site and anyone can try to solve them.Back in 2015, the number-one ranked data scientist on the website was an engineer in Brazil.

Michael Smith: And all of a sudden he was getting job offers from Silicon Valley companies. Not because of his degree, not because of his job experience, but because they could see based on his Kaggle rating that he was a really good data scientist.

Céline Gounder: So… if Big Tech and alternative certifications are on the heels of traditional universities during the pandemic… what changes could help universities survive and meet the needs of their students beyond the pandemic? That’s after the break.

Céline Gounder: “Verified”, the investigated documentary podcast from Witness Doc, is back to ask tough questions about who we trust and why. Hosted again by reporter Natasha Del Toro, this new season investigates whether a group of women developed ovarian cancer from dusting their bodies with Johnson & Johnson’s baby powder. Perhaps it’s most iconic product, and one that’s been selling since the 1800s. One woman’s mysterious illness falls into thousands of court cases, each claiming that baby powder is to blame for their cancer. “Verified: Dust Up”, is the story of a trusted brands fight to convince consumers and speculators that baby powder is safe and to discredit the work of the scientists who claim it isn’t. Verified follows this decade-long story to ask, could this product so many of us have in our medicine cabinets be putting us at risk? Listen and subscribe to “Verified: Dust Up” right now on Stitcher, Apple Podcasts, or wherever you find your podcasts.

Céline Gounder: The pandemic forced a lot of universities to go online all the sudden. But that hasn’t been a good experience for a lot of students. As an instructor, Michael has his own gripes about online education.

Michael Smith: Lots of things suck about online education. I miss the energy of the students in the classroom. The other thing that sucks about online education today is we’re doing exactly what every other industry has done when they saw a new technology. So iTunes became a way to sell the CDs I’ve always sold in a digital format. And it was fine, but it wasn’t really making the best use of the medium. It really took Spotify and Netflix to think hard about, you know, we don’t actually want to sell albums. We want to give you access to all the world’s music. What we haven’t created yet is the Netflix or Spotify of education.

Céline Gounder: One educational startup that’s getting a lot of attention is called Outlier.

[clip from promo video for calculus: https://www.outlier.org/products/calculus-i]

Scott Galloway: Calculus has been taught the same way for a hundred years. It hasn’t changed. And calculus is like a $7 billion business, Find the best calculus instructor in the world, put in place incredible production values, and teach it for a 10th of the cost and let the kids get credits from University of Pittsburgh, you paid $400 for calculus instead $4,000.

[clip from promo video for calculus]

Céline Gounder: Whether it’s Outlier or another company, remote learning needs a killer app to break into the wider market. Until then, people aren’t too wild about online learning. The Pew Research Center reported in October that only 30 percent of U.S. adults surveyed thought online courses offered the same educational value as in-person learning. But Michael says that 30 percent might be an important tipping point.

Michael Smith: New online platforms don’t have to be as good as the residential experience. They just have to be good enough while costing less than a hundred thousand dollars and taking less than four years of a student’s time.

Céline Gounder: Michael says this is a great example of disruptive innovation, the theory coined by Clayton Christensen.

Michael Smith: To me, the real genius of his disruptive change theory is, he noticed this pattern where companies would fail because they only focused on the needs of their existing customers. They ignored how new technologies could serve the needs of a whole new customer group. And then they ignored the fact that those new technologies would get better fast enough so that it would start to siphon away some of their existing customers.

Céline Gounder: In the near future, residential college experience may be better than online. But there’s a large group of potential students out there — maybe the “Will Huntings” of the world — who don’t have the time or the money to attend a 4-year institution.

Michael Smith: We ought to be thinking really hard about the people who don’t have the opportunity to come to our campus and what are they going to do in this new technological world?

Céline Gounder: Michael says this kind of disruption looks a lot like what happened to the music industry as mp3’s were starting to become popular. He interviewed someone who created a platform that would allow record companies to sell digital music online before iTunes.

Michael Smith: And when he showed this to a, a record exec the record executive listened to the audio quality of the file, the digital file. And he said, “No, one’s going to listen to that crap.” He actually used a slightly more colorful word than that, but that was the basic idea is that this doesn’t have anywhere near the audio quality that my consumers demand from CDs. Even though the audio quality wasn’t as good the experience actually was much better for the consumer. Even though it had lower audio quality created value for consumers, in a whole bunch of new ways. And, and that’s, that’s the lesson of the music industry is that by focusing on the traditional way, quality was delivered, they missed the point about the new quality that could be provided.

Céline Gounder: And this disruption has already started in academia. Michael has been studying how technology transformed one university and destroyed another. In 1996, Paul LeBlanc became President of a small liberal arts college in Vermont called Marlboro College. The college had been struggling with enrollment, and Paul wanted to implement his vision to re-invent the college for the age of the internet. The board was not impressed. In 2003, Paul left Marlboro to become President at Southern New Hampshire University.

Michael Smith: Today, Southern New Hampshire University is one of the most powerful universities when it comes to online education. Paul Leblanc, increased their enrollment from 3,000 students to 135,000 studentsand Southern New Hampshire projects that it will have 300,000 students by 2023. So Southern New Hampshire, by being willing to change their business model to pursue their mission of educating students is doing really well.

Céline Gounder: What happened to Marlboro College? It ceased all operations in August. When it closed, it had just 150 students. Michael is bullish on online education.

Michael Smith: It’s invigorating because I think these new platforms are going to open up a lot of opportunity for students.

Céline Gounder: But he has his doubts too.

Michael Smith: Um, it’s terrifying because I am worried that we’re going to get away from some of the things that have created, you know, some common body of knowledge in our students.

Céline Gounder: Degrees or certifications that are narrowly tailored may be better for students’ time and wallets… but it runs the risk of creating the same kinds of echo chambers as social media.

Michael Smith: I am a little bit worried we’re going to lose out on some of those opportunities to broaden people’s horizons.

Céline Gounder: There are also practical limitations for online learning.

Scott Galloway: It’s very hard to teach someone how to place a syringe, uh, using Microsoft Teams. So nursing schools, welding schools, aesthetician schools, the vocational schools are, you know, just get taking such a beating. And by the way, who typically, who typically on average goes to university? Kids from middle and upper income households. Who typically goes to more vocational training kids from lower and middle-income households. So we have some very unhealthy trends that continue to thrust into the future on income inequality.

Céline Gounder: But despite these drawbacks, Michael and Scott both think the disruption caused by the pandemic could have a positive impact on higher education in the long run.

Scott Galloway: So I think there’s an opportunity to dramatically expand enrollments using small and big tech. Dramatically decreased costs and move back to where we were at the last half of the 20th century, where education was the primary vehicle for upward mobility. That we weren’t as freakishly in love with the top 1% but we said to people, maybe there’s an opportunity for you to get into the 1% at some point in your life. And we’re going to take risks on people.

Céline Gounder: “Epidemic” is brought to you by Just Human Productions. We’re funded in part by listeners like you. We’re powered and distributed by Simplecast.

Today’s episode was produced by Zach Dyer and me. Our music is by the Blue Dot Sessions. Our interns are TabataGordillo, Annabel Chen, and Bryan Chen.

If you enjoy the show, please tell a friend about it today. And if you haven’t already done so, leave us a review on Apple Podcasts. It helps more people find out about the show!

And Just Human Productions is now on Instagram! Check us out @justhumanproductions to learn more about the characters and big ideas we cover on EPIDEMIC and our sister podcast AMERICAN DIAGNOSIS.

You can learn more about this podcast, how to engage with us on social media, and how to support the podcast at epidemic.fm. That’s epidemic.fm. Just Human Productions is a 501(c)(3) non-profit organization, so your donations to support our podcasts are tax-deductible. Go to epidemic.fm to make a donation.

We release “Epidemic” every Friday. But producing a podcast costs money… we’ve got to pay our staff! So please make a donation to help us keep this going.

And check out our sister podcast “American Diagnosis.” You can find it wherever you listen to podcasts or at americandiagnosis.fm. On “American Diagnosis,” we cover some of the biggest public health challenges affecting the nation today. In Season 1, we covered youth and mental health; in season 2, the opioid overdose crisis; and in season 3, gun violence in America.