S4E6: Right to Water / Ernestine Chaco, Brianna Johnson, George McGraw, Jeanette Wolfley, Zoel Zohnnie

In 2020, during the first wave of the coronavirus pandemic, Zoel Zohnnie was feeling restless. Growing up on the Navajo Nation, he said, the importance of caring for family and community was instilled at an early age. So Zohnnie wanted to find a way to help members of his tribe. One need in particular stood out: water.

American Indian and Alaska Native households are 3.7 times more likely to lack complete plumbing compared with households whose members do not identify as Indigenous or Black, according to a 2019 mapping report on plumbing poverty in the United States.

“Climate change and excessive water use is exacerbating these struggles,” explained George McGraw, CEO of DigDeep. “Much of the western United States has been in severe drought for years. Many rivers and wells on or near the Navajo land have dried up. As groundwater recedes, people are forced to seek water from unsafe sources.”

To answer that need, Zohnnie began hauling water to people who were without, and he founded Water Warriors United. In this episode, listeners come along for the ride as he ― and his truck ― make one herculean trek across snow-covered roads in New Mexico.

Episode 6 is an exploration of the root causes behind the Navajo Nation’s water accessibility challenges and a story about the water rights that some communities have effectively lost.

–

Season 4 of “American Diagnosis” is a co-production of KHN and Just Human Productions.

Our Editorial Advisory Board includes Jourdan Bennett-Begaye, Alastair Bitsóí, and Bryan Pollard.

To hear all KHN podcasts, click here.

American Diagnosis Podcast

Season 4 Episode 6: Right to Water

Air date: March 29, 2022

Editor’s Note: If you are able, we encourage you to listen to the audio of American Diagnosis, which includes emotion and emphasis not found in the transcript. Transcripts are generated using a combination of speech recognition software and human transcribers and may contain errors. Please use the transcript as a tool but check the corresponding audio before quoting the podcast.

TRANSCRIPT

Zoel Zohnnie: It’s, like, perfect. Even though it snowed, the sun’s out.

Céline Gounder: This is Zoel Zohnnie. It’s early in the morning, and he’s got his hands full. One hand holds a breakfast burrito; the other is on the wheel of a black truck towing a thousand gallons of water. The side of the truck reads, “Water Warriors.”

Zoel delivers water to families all across the Navajo Nation, families that don’t have running water. On this morning in December 2021, he’s in the northwest corner of New Mexico. Browns and oranges blanket the landscape. Freshly fallen snow glitters in the morning sunlight. But the ground underneath his truck is not so nice. Zoel just ran into some trouble …

Zoel Zohnnie: Ah, crap. This is not good. I’m just sliding back. Like, if that trailer decides to go one way or another, my wheels are like this, but it’s just going out …

[Audio of transmission whirling]

Céline Gounder: Audio producer Georgina Hahn is riding along this morning.

[Audio of transmission vrooms as wheels spin]

Georgina Hahn: The mud flying was pretty epic. [laughs]

Céline Gounder: The road’s washed out, and the wheels are spinning in the mud. Zoel gets out to see what’s wrong.

Zoel Zohnnie: The truck’s just too heavy. The trailer is too heavy. I think what we’re going to end up having to do is back up and try to make a run at it.

Céline Gounder: Zoel has got to find a way to get this truck up the hill. Some families there have been waiting weeks for this water.

40% of those living on the Navajo reservation don’t have access to running water. That’s perhaps 69,000 people based on 2010 census estimates. And in 2020, the president of the Navajo Nation told lawmakers that in one community on the Arizona-Utah border, upwards of 900 people rely on a single roadside spigot for their water.

Zoel knows that way of life.

Zoel Zohnnie: There was a time when we struggled and we had to move out to — we call it sheep camp, out by the ranch where we kept the livestock. And so when we moved out there, there was no running water or electricity yet. So there was a period of time where my sister and my mom and our family, we had to move out and kind of live off the land, I guess.

Céline Gounder: Living at the sheep camp as kids, it was Zoel and his sister’s job to haul water. Enough for themselves — and the animals.

Zoel Zohnnie: So that’s kind of what shed some light on the needs for people who were needing drinking water during the pandemic in remote areas.

Céline Gounder: When Zoel was laid off from his welding job at the beginning of the pandemic, he wanted to help his tribe somehow. He was already delivering firewood to elders he knows. So, he started trucking water to them, too.

Zoel Zohnnie: The Navajo Nation and its struggles during the pandemic became the story. The lack of infrastructure, the need for health, the need for water. And so now that the pandemic is kind of not at its height, the story has moved on. But we’re still here. Same problems, same struggles.

[Theme music up]

Céline Gounder: Water access on the Navajo Nation, and other tribal lands in the United States, has been shaped by Supreme Court cases and federal and state policy that largely left tribal communities out of critical access to water. In this episode, we’ll learn what it takes for some people on the Navajo Nation to get drinking water.

Brianna Johnson: They saved up milk containers and use those to haul their own water in.

Céline Gounder: How we got here in the first place…

Jeanette Wolfley: You see all these reservoirs around the West. Most of them are built for municipalities, for states, for mining companies — all non-Indian use. It was never built for tribes.

Céline Gounder: And what’s being done to fix it.

George McGraw: Once people get over the shock and surprise that this problem even exists in their backyards, they’re immediately motivated to help.

Céline Gounder: I’m Dr. Céline Gounder and this is American Diagnosis.

[Theme music out]

Céline Gounder: Back in 2020, when much of his hometown of Tuba City, Arizona, was in lockdown, Zoel was restless. He was worried about coronavirus, for sure — he says he has respiratory issues — but he kept thinking there was something more he could do. That mentality comes from his mom.

Zoel Zohnnie: For me, she would always chase me outside to help. And the way she would say it was, “There’s nothing wrong with you. You’re perfectly capable. You’re able body, get out there and go help.”

Céline Gounder: Growing up on the Navajo Nation, caring for family and community was instilled at an early age.

Zoel Zohnnie: For me, it goes down even further, into the roots of resiliency. When we know we are standing on our own two feet and we have to help do for ourselves and, you know, we can do it. We are a tribe, we are a people. So all those things kind of blossomed from what my mom taught me.

Céline Gounder: All this was going through Zoel’s mind when he was stuck at home.

Zoel Zohnnie: I thought on it for about a week. And I’m not sure exactly how, but I saw people delivering water in pallets with water bottles and cases and things like that. And it just kind of went off like a lightbulb in my head.

Céline Gounder: Zoel dove headfirst into this new project. He collected donations and bought a water tank that could fit in the bed of his truck. Through word of mouth, more donations came in. Other people volunteered to deliver water. Now, Water Warriors [United] has four trucks delivering water.

Zoel Zohnnie: So that’s kind of how it started, in that small area. And then as it grew through social media, the presence grew, and the work was seen. Then other communities would reach out, and they would say, “Hey, I’m from this community. We have this many elders that don’t have water. Is there any way you can make time to come down and help us out?”

Céline Gounder: Hauling water is nothing new on the Navajo Nation. If families don’t have a well or access to waterlines, many go to water stations maintained by the Indian Health Service. But during the pandemic, people were wary of these communal spaces. A routine trip to get water for drinking, cooking, and bathing suddenly came with the risk of catching covid.

On one of the first deliveries he made, Zoel showed up at the home of an elder just as a daughter was about to leave to haul water for her father. Zoel remembers her relief when she saw his truck pull up.

Zoel Zohnnie: She’s like, “Oh, that’s great! Now I can run to town and I can do this. And, you know, three extra hours in my day that I can, you know, do these other things with and get groceries or, you know, stuff to help them out.” So it kind of has a ripple effect with everybody.

Céline Gounder: Struggles to get water ripple into public health, too.

George McGraw: Water touches every aspect. And something unfortunately that many of us take for granted.

Céline Gounder: That’s George McGraw. He founded the nonprofit DigDeep. It’s an organization that helps families on the Navajo Nation gain access to running water through the Indigenous-led Navajo Water Project.

George McGraw: We use water to bathe and to cook and obviously to drink, but having water at home is what enables people to pursue an education and go to school. It’s what enables people to have a job and an income. Actually not having to collect water or worry about where it’s coming from or be sick because you’re drinking dirty water is what gives you the time you need to play with your kids. It’s absolutely everything.

Céline Gounder: The public health impacts of this lack of water can quickly snowball. George learned this his first day on the Navajo Nation in 2014. He was riding alongside a school bus driver who delivered water in her free time. They met a woman named Brenda.

George McGraw: And Brenda ran out of the house, and she filled up a kitchen pot, like, right at the truck. And she brought it into the kitchen, and she started making tamales. And I asked her, like, “Oh, this is cool. Like, are you having family over later or …?” She’s like, “No, no, I’m going to sell these.”

Céline Gounder: Brenda told George she sold tamales just down the hill. She used the tamale money to buy gas for their family’s truck.

George McGraw: I was like, “Oh, that’s great. Then you can sort of get around.” And she looked at me like, “You don’t get it.” [Soft music up] “My husband works at a processing plant in Gallup, which is 50 miles away. And he drives there to work. He was injured on the job. He came home. We didn’t have the water we needed to keep his foot injury clean, so it got gangrene. So we go to the hospital. He’s in the hospital for a month with this infection. He was discharged from the hospital 10 days ago, and he’s been sleeping on the streets of Gallup because no water meant no tamales, and no tamales meant no gas money, and no gas money meant I couldn’t pick up my husband, and without picking up my husband, he couldn’t work. And so now we’re behind.”

Céline Gounder: Climate change and excessive water use are exacerbating these struggles, George says. Much of the western United States has been in severe drought for years. Many rivers and wells on or near the Navajo land have dried up. As groundwater recedes, people are forced to seek water from unsafe sources.

George McGraw: A lot of folks we work with get water on foot, or on horseback, or drive and pull water out of, I don’t know, sometimes an unregulated well, or the spigot on the side of a building, or even like a livestock pond, or a trough, or a windmill that could be contaminated with uranium or arsenic and make them really sick.

Céline Gounder: Lack of water can also contribute to chronic health problems.

George McGraw: Those that are lucky enough to be able to travel and afford water are buying bottled water at the store, and it’s costing a lot of money and are often tempted to buy sugar-sweetened beverages instead. So we’re looking at a huge incidence of diabetes in these homes because in some cases, sugary beverages are cheaper than packaged water.

Céline Gounder: George says not having easy access to safe water weighs on people’s mental health, too.

George McGraw: We talk to people who work in places like the Navajo Nation all the time. They’re working with, especially young people, who feel really trapped by this reality.

[Audio of transmission whirring fades up.]

Céline Gounder: Back on the road, Zoel and producer Georgina Hahn got the truck moving again.

Zoel Zohnnie: We threw it in four-wheel drive and eventually just had to floor it and inch our way up the hill. That was probably the hardest fight that we ever had, or I’ve ever had, with any of the vehicles that I’ve driven the whole time that I’ve been taking water out.

Céline Gounder: They were on their way to Sheep Springs, New Mexico, to make the first deliveries of the day.

[On-scene audio of Zoel and Georgina saying “hi, hello” to water recipients.]

Céline Gounder: Brianna Johnson — a local community health representative — is bundled up against the cold and waiting for Zoel.

Zoel Zohnnie: The road was just too …

Brianna Johnson: Oh no …

Zoel Zohnnie: I might’ve damaged the truck, actually. But we’ll figure that out if that, if that’s the case.

Céline Gounder: Brianna works for the Naschitti Chapter, one of the communities on the reservation. Zoel and Brianna decide how to divvy the water.

Zoel Zohnnie: Who — are they all — who has the most people in it? All the same? So we could do 300, 250 gallons each.

Céline Gounder: They want to make sure they can stretch the water as far as possible.

Zoel Zohnnie: It’s either give them all a little bit today or just get half of them today and leave the rest kind of stuck.

Brianna Johnson: I think the 250 each.

Zoel Zohnnie: OK. Let’s do that.

[Audio of truck engine, machine beeping]

Céline Gounder: Zoel Zohnnie has finally arrived at the home of Sara and Betty Johnson. Dogs bark as the truck pulls up. The sisters are in their 70s, but you’d never know it from their chores. When Zoel arrives, Sara is chopping wood.

Sara Johnson: Yeah, chopping some wood before the wind hits! [laughs]

Céline Gounder: Sara’s voice is muffled from the scarf around her face. She points to one of their cistern tanks.

Sara Johnson: I don’t know about that middle one. I don’t know if it has water or it’s low.

Céline Gounder: Zoel gets out and starts to fill it.

[Audio of water rushing, splashing.]

Céline Gounder: People who grew up in cities might not be familiar with a cistern. Those are underground storage tanks that hold water for a home. Congress passed a law in 1959 that empowered IHS to provide essential water and sanitation services to American Indians and Alaska Natives. The going has been slow getting cisterns and other water infrastructure out. Sara and Betty got their cistern just a year before we recorded this interview.

Betty says the cisterns made a big difference.

Betty Johnson: We didn’t have no water. Somebody has to haul water every day, two days, three days. That’s the way it used to be. Now, it’s nice.

Georgina Hahn: Before, they used to just haul their own water, because they would use smaller containers, kind of like 5-gallon buckets down to, like, milk containers, and use those to haul their own water in. That’s what they were using before.

Céline Gounder: These cisterns can hold upwards of 1,100 gallons, Brianna says. The average American family uses more than 300 gallons of water a day, according to the Environmental Protection Agency. The families on Zoel’s delivery schedule today may have to make 250 gallons last for weeks.

Zoel Zohnnie: Typically, we try to get there every three weeks, but during the winter times, it’s once a month or even, you know, once every five or six weeks.

Céline Gounder: These households can store the water they need. But they still have to rely on a service like Zoel’s to keep them full. The sisters are still careful with their water, especially in winter, when it’s hard to get water delivered, as Zoel just found out.

Sara Johnson: I try to save my water for December, January until spring comes around. [laughs]

Betty Johnson: [laughs with her sister] Yeah, yeah …

Céline Gounder: There are water stations around the Navajo Nation installed by the Indian Health Service where families can fill water containers. But Brianna says they’re unreliable. Sometimes they’re out of order, damaged, or vandalized. Until there’s a permanent solution, Brianna says, elders like Sara and Betty will have to keep relying on deliveries from Zoel.

Brianna Johnson: I hope Zoel does this for a long time because I honestly wouldn’t know what they would do or how they would hold their own water if Zoel wasn’t doing any of this.

Céline Gounder: Families are going to these lengths because their homes aren’t connected to public water utilities. So, what’s preventing the Diné and other Native people in the western United States from getting access to clean running water? We’ll find out, after the break.

[MIDROLL – theme music plays]

Céline Gounder: Jeanette Wolfley is a member of the Shoshone-Bannock tribe in Fort Hall, Idaho. When I spoke with her, she was also an associate professor of law at the University of New Mexico, where she taught natural-resource and federal-Indian law. Jeanette says access to water comes down to one thing.

Jeanette Wolfley: Well, the biggest obstacle is that there’s not a lot of water to go around, particularly in the West.

Céline Gounder: Jeanette says this water story starts with something we haven’t talked much about in this series, a legal victory for tribes: a Supreme Court case from 1908 called Winters v. United States. The case decided that when the federal government created a reservation, the tribes were entitled to any water they needed. Basically, there’s no reservation without water. This was a big win. The Winters case established that tribes had something called senior water rights. This means tribes have first dibs on the water they need.

Jeanette Wolfley: The case would have allowed them then to begin using and filing claims to their senior water rights to gain millions of acres of water. But …

Céline Gounder: There’s always a “but.”

Jeanette Wolfley: But no one told them they needed to do that. Or that, “You better start securing water for your reservation, or it’s not going to be there because everybody else is using it or taking it.”

Céline Gounder: The federal government may have sided with Indigenous people seeking access to water in the Winters decision, but that assistance stopped there. Instead, over the next 50 years, as more Americans moved into Western states, the federal government started damming rivers and building massive reservoirs.

DAM ARCHIVE AUDIO: Bordering on the vast space of the Navajo reservation, the dam site soon became the objective of a slowly growing army of construction experts.

Céline Gounder: Like the Hoover Dam …

DAM ARCHIVE AUDIO: A modern colossus, shouldering the rock-ribbed walls of Black Canyon, stemming and controlling the floods, and bending the will of a hitherto ungovernable stream: the Colorado River. To perform the fruitful tasks of a civilization rapidly invading the limits of its last frontier.

Céline Gounder: Glen Canyon Dam …

DAM ARCHIVE AUDIO: The dam will back up the river for a distance of 186 miles. It will store enough water to cover the entire state of Pennsylvania to the depth of 1 foot.

Jeanette Wolfley: You see all these reservoirs around the West. Most of them are built by the United States for municipalities, for states, for mining companies, for agricultural. All non-Indian use. It was never built for tribes.

Céline Gounder: The reservoirs provided the water and the hydropowered electricity that allowed Western states to flourish.

Jeanette Wolfley: They began appropriating the water or taking the water and using it to basically provide for cities, provide for swimming pools and everything else. Luxuries that …

Céline Gounder: Golf courses?

Jeanette Wolfley: Golf courses. [Jeanette and Céline laugh.] Luxuries that people probably never thought it would be used for, you know. Instead of just the day-to-day kind of drinking water purposes or for agriculture purposes.

Céline Gounder: Jeanette says, by and large, Indigenous communities were passed over.

Jeanette Wolfley: So, it wasn’t until beginning, say, in the 1960s that then tribes began to say, “Well, wait a minute. Where’s the water that we need?”

Céline Gounder: Tribes had senior rights to the water, but by that point almost all that water had been spoken for decades before.

Jeanette Wolfley: It’s called, like, a paper water right, that you have it on paper, that you have the right, but you don’t actually have a wet water right that is actually flowing down into your irrigation ditches.

Céline Gounder: Take the Colorado River Comact of 1922. California, Arizona, Nevada, Utah, Wyoming, Colorado, and New Mexico got together and carved up the water from the Colorado River. That water made it possible for cities like Los Angeles, San Diego, Phoenix, and Las Vegas to thrive. Tribes like the Diné were never consulted.

Jeanette Wolfley: The tribes are trying to get a piece of the pie, but they’re coming kind of late.

Céline Gounder: If tribes can secure the rights to water, there’s still the trouble of getting it to homes. On the eastern end of the Navajo Nation, not too far from where Betty and Sara live, the relics of a 19th century law have made it very difficult to build infrastructure like water lines that could bring water directly to people’s homes.

Dr. Ernestine Chaco: So when we talk about these big concepts of access to water, access to electricity, we have to talk about land status.

Céline Gounder: That’s Dr. Ernestine Chaco, a Diné lawyer and physician. We spoke with her in our first episode. Ernestine says building on reservations, what’s known as tribal trust land, requires permission from the federal government. But there’s other kinds of land on the Navajo Nation.

Dr. Ernestine Chaco: You have some private lands. Some people do have the ability to buy private land on the reservation, like pieces of it. There’s public land on there, too, there’s state land. Then sometimes there’s allotment land.

Céline Gounder: Allotment land was created when Congress passed something called the General Allotment Act of 1887. It’s better known as the Dawes Act, named after its sponsor, Massachusetts Sen. Henry Dawes. Historians say it was a bid to push Native people to assimilate. The idea was to parcel out reservations into smaller plots — or allotments — to individual members of the tribe. By forcing Indigenous people out of collective land ownership, Congress thought Native people would emulate the way white settlers lived on the land.

Open Google Maps and look up the Navajo Nation. When you see the eastern end, especially in New Mexico, zoom in. You’ll see all these little squares, almost like the reservation has somehow become pixelated. Out here, it’s called a checkerboard. Those are portions of land that were allotted or sold or lost.

As portions of the reservation were privatized, many Indigenous people lost their land. They didn’t know they had to pay taxes on it, so sometimes it was repossessed and sold. Between 1887 and 1934, when the allotment period ended, nearly two-thirds of the land parcels passed into non-Native ownership.

The allotment system created another problem when it comes to water infrastructure, an exponential number of owners. Ernestine explains.

Dr. Ernestine Chaco: If you have three kids, then that allotment land is broken up into thirds. And let’s say those three kids have more kids — say they have nine kids. Then that land is broken up into nine people. Let’s say they have kids themselves … [Audio fades out under Céline]

Céline Gounder: So while the number of heirs keeps going up, the land is still the same size as it was at the start. Until …

Dr. Ernestine Chaco: […] Let’s say in the fifth generation, you have 81 people in that generation. Then that piece of land then now belongs to 81 people. And so if you’re going to try to put a pipeline through that area, you have to get consent from those 81 people. So if one person says “no,” you can’t build through that land.

Céline Gounder: More than 200 miles away, in the western end of the Navajo Nation, there’s another problem that keeps water from people who need it.

It started with a land dispute between the Navajo Nation and the Hopi Tribe. Both tribes claimed a large portion of land in eastern Arizona. In an attempt to push the tribes to negotiate, the commissioner of Indian affairs, Robert Bennett, banned all new construction on that contested land in 1966. It became known as the Bennett Freeze.

The freeze was all-encompassing. Residents weren’t allowed to make simple household repairs, much less build a water pipeline. Tribal governments say the Bennett Freeze sealed 1.6 million acres in poverty for 40 years.

The tribes reached a resolution in 2009, and President Barack Obama lifted the freeze. But no funds have been allocated for the redevelopment of that land since.

All this history has created an environment that makes reliable water access incredibly difficult for many living on the Navajo Nation. In the face of these obstacles, hauling water by truck is still how many get the water they need for drinking, sanitation, and bathing.

[Audio of news clip of Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act signing; clapping.]

Céline Gounder: On Nov. 15, 2021, President Joe Biden signed the $1.2 trillion Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act into law. It’s massive, and it’s going to affect a lot of communities.

George McGraw, the founder of DigDeep, the water-access advocacy organization, says there’s a lot of money set aside for improving sanitation on tribal lands.

George McGraw: So one of the coolest parts in my, like, wonky mind of this infrastructure bill is $3.5 billion will go to [Department of] Health and Human Services, and it will specifically go to the Indian Health Service to fund what they call the sanitation construction facilities backlog.

Céline Gounder: Since 1989, the health service has kept a list of all the water and sanitation projects needed across Native lands in the United States, everything from water treatment plants to community bathrooms.

George McGraw: Congress has been continually appropriating just a small percentage of the money that IHS requests every year, for decades — not even enough to keep up with the pace of the growth in the list. So every year, even though they get a little bit of money, the list gets longer.

Céline Gounder: According to a 2019 IHS report, there are more than $500 million worth of needed water and sanitation projects on the Navajo Nation alone. George is encouraged by the funds but says it’ll be a huge undertaking to actually get these projects built.

George McGraw: And I think the key to success is going to be a real partnership between the federal government and tribal government, one in which both recognize each other as equals and in which, you know, tribal, especially local and community voices, are really centered. So that when people get access, it’s the access that they need and that fits their lives and lifestyles and isn’t just, you know, some project that a bureaucrat seven states away wrote on paper.

Céline Gounder: Meanwhile, Zoel Zohnnie isn’t waiting. He’ll keep delivering water. Back at Sara and Betty’s home on the Navajo Nation, he has finished filling the cisterns.

Zoel Zohnnie: We put some in there.

Sara Johnson: Oh, you already did?

Zoel Zohnnie: About 250. Maybe close to 275.

Sara Johnson: Ahhh.

Zoel Zohnnie: Can I take your picture chopping wood?

Sara Johnson: OK!

Zoel Zohnnie: Wait, just sit right there. Right there. [laughs]

Céline Gounder: Zoel teases Sara like she’s family.

Zoel Zohnnie: OK. Now, I’ll take one of you chopping so we can tell our kids out there to get to work!

[Audio of everyone laughing]

Zoel Zohnnie: We’ll be back probably, I think, next week, once the road’s better and it’s safer.

Sara: OK. [Speaks to Zoel in Navajo]. Thank you for bringing the water for us again.

Céline Gounder: A few months later, we called Zoel up and asked him to talk about what’s on his mind as he inches along on the bumpy roads toward his next delivery.

Zoel Zohnnie: These elders that we help, they’ve made it farther than we have. They’ve gone through all these struggles that we’re just now learning about or that we’re still fighting through. And they survived. And that in itself is a triumph. And for them to be there, you know, making their way or needing the help that we can provide and for us to be able to show up and laugh and talk with them and hear the stories that they have and just to be kind of there in a good way, it’s extremely impactful to a lot of us, me especially. It is just a heartwarming experience and heartwarming feeling to be able to give the right people the right help at the right time.

[Truck sounds fade out into end theme]

CREDITS

This season of American Diagnosis is a co-production of Kaiser Health News and Just Human Productions. Additional support provided by the Burroughs Wellcome Fund and Open Society Foundations. This episode of American Diagnosis was produced by Mary Mathis, Zach Dyer, and me. Additional reporting by Georgina Hahn. Special thanks to Andrew Curley. We’re funded in part by listeners like you. We’re powered and distributed by Simplecast.

Our Editorial Advisory Board includes Jourdan Bennett-Begaye, Alastair Bitsóí, and Bryan Pollard. Taunya English is our managing editor. Oona Tempest does original illustrations for each of our episodes. Our intern is Bryan Chen.

Our theme music is by Alan Vest. Additional music from the Blue Dot Sessions.

If you enjoy the show, please tell a friend about it today. And if you haven’t already done so, leave us a review on Apple Podcasts. It helps more people find out about the show!

The An Arm and a Leg podcast is another Kaiser Health News show we think you’ll like. It’s about the cost of health care and, importantly, about what consumers can do about it. If you have a health care story to tell, join host Dan Weissmann. He’s gathering a community to offer empathy, and sometimes a good, dark laugh about our health system.

Follow Just Human Productions on Twitter and Instagram to learn more about the characters and big ideas you hear on the podcast. And follow Kaiser Health News on Twitter, Instagram, and Facebook. Subscribe to our newsletters at khn.org so you never miss what’s new and important in American health care, health policy, and public health news.

I’m Dr. Céline Gounder. Thanks for listening to American Diagnosis.

END

Guests

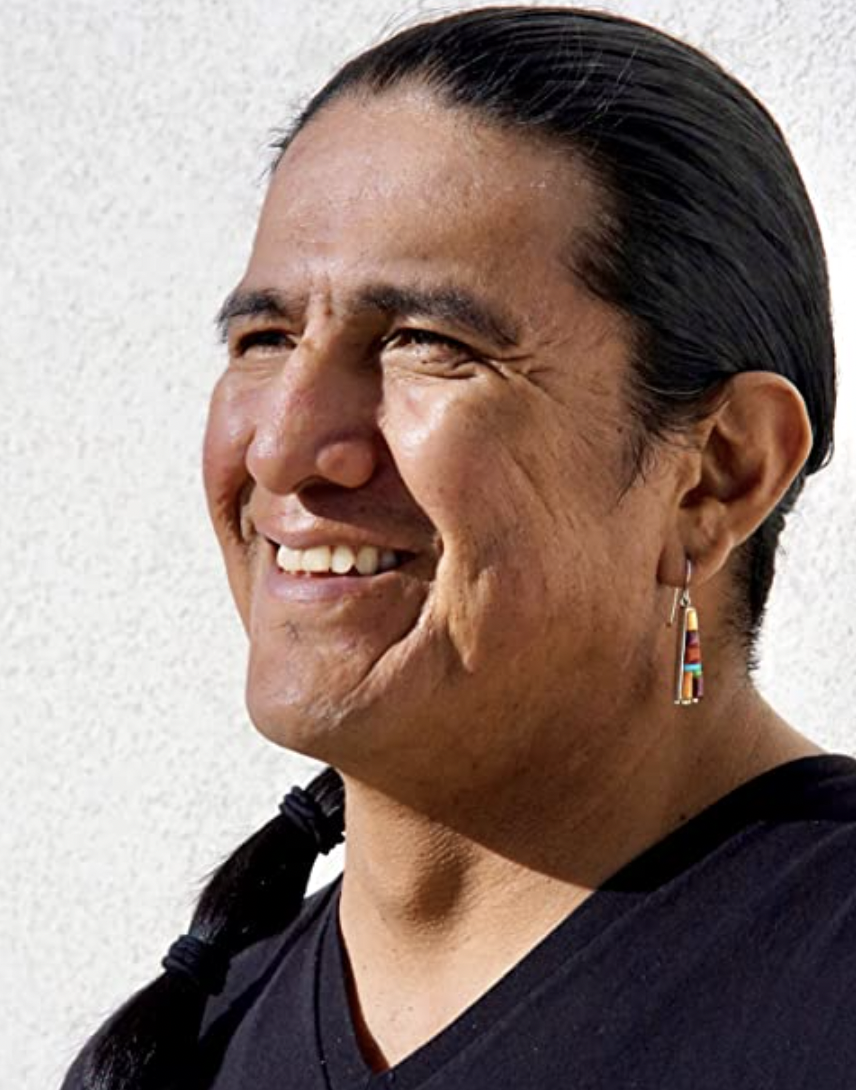

Zoel Zohnnie

Zoel Zohnnie